In Brazil, 2026 has begun with two major institutional shifts that threaten to redefine how large-scale projects advance in the Amazon, while drastically weakening the socioenvironmental safeguards meant to protect forests and peoples.

Days after the close of the COP30 climate summit, a large majority in Brazil’s Congress overrode President Lula’s vetoes of the General Environmental Licensing Law, popularly known as the “Devastation Law“. Driven by agribusiness and other land-hungry economic sectors, lawmakers pushed through a framework that recklessly slashes licensing processes designed to prevent harm and protect the environment. With the law now in effect, mechanisms such as “License by Adhesion and Commitment” allow companies to bypass regulatory agencies and rapidly “self-license” most projects, even when they carry serious social and environmental risks.

The new law also shifts oversight of environmental licensing from the federal government to the states, strips authority from federal bodies such as the National Environmental Council, and weakens consultation with Indigenous peoples and affected quilombola (Afro-descendant) communities. Its capacity to fast-track highly destructive projects with minimal oversight cannot be overstated. The implications for the Amazon and its peoples are profound.

At the same time, as 2025 drew to a close, Brazil’s Supreme Court (STF) resumed its perilous debate over Indigenous territorial rights. Although a recent ruling reaffirmed that the specious “time-limit” (Marco Temporal) thesis is unconstitutional, it simultaneously weakened the constitutional framework that has protected Indigenous rights and enabled the demarcation of traditional territories since 1988. Authored by Justice Gilmar Mendes, who has a long record of anti-Indigenous positions, the ruling dismantles fundamental land rights protections.

One clause establishes that Indigenous peoples who do not formally submit land claims within one year will lose the right to have their territories demarcated. Rather than treating demarcation as a distinct, constitutionally protected process grounded in Indigenous identity and ancestral rights, these claims would be diverted into the government’s “social interest land expropriation” framework. That system is rooted in Brazil’s controversial agrarian reform model, created to address landlessness among rural workers, not to recognize and protect Indigenous territories.

The ruling also prohibits land reclamation actions, a political strategy that has been central to Brazil’s Indigenous movements since the promulgation of the 1988 Constitution. Autonomous land recovery and territorial monitoring have long pressed the government to enforce Indigenous rights. Removing this tool makes formal demarcation far less likely to advance. The ruling constitutes a direct attack on Indigenous peoples, environmental protection, and climate stability.

The realistic outlook for Brazil in 2026 is one in which large-scale infrastructure and extractive projects move forward with drastically reduced safeguards and public oversight. Territories and communities will be more exposed to invasion and to the appropriation of natural resources by companies and the government. The erosion of protections is likely to deepen rights violations and intensify social conflicts, placing even greater strain on the judiciary, which will be forced to mediate disputes without adequate legal frameworks.

For Amazon Watch’s priority campaigns, this scenario is far from abstract. It reshapes the balance of power around extractive projects and accelerates political timelines. It also creates a serious risk that legal changes will be exploited as shortcuts for high-impact, high-conflict ventures.

Belo Sun Mining, a Canadian company seeking to carve Brazil’s largest open-pit gold mine into the banks of the Xingu River, illustrates this threat clearly. As gold prices continue to rise, the company could seek to have its project classified by Pará state regulators as “strategic.” Under the Devastation Law, that designation would open the door to a new fast-track procedure known as “Special Environmental Licensing.”

In this scenario, Belo Sun’s complex and contentious 13-year licensing process, which Brazilian social movements and courts have repeatedly and successfully challenged, could be wiped clean and restarted under a drastically weakened regulatory regime. The risks this poses to the Volta Grande do Xingu, and to other territories being positioned as sacrifice zones for extraction, are immediate and concrete.

The Ferrogrão mega-railway offers another warning sign. Pressure from sectors of the federal government and from the agribusiness lobby has produced an institutional paradox. While the project remains blocked by a Supreme Court injunction, and despite the Lula administration’s commitments to revise studies and guarantee consultation of threatened communities, federal agencies are already advancing pre-concession steps.

At the end of 2025, Brazil’s National Land Transport Agency submitted the project’s environmental studies, commissioned by the Ministry of Transport to the Federal Court of Accounts. This occurred despite warnings from research institutions that the studies are incomplete and methodologically flawed. These steps are clear precursors to licensing a highly destructive and socially divisive mega-project. In a context of weakened environmental standards, the threat is acute.

This push is unfolding as one of the few private mechanisms that helped curb the direct link between soy and Amazon deforestation is being dismantled. This month, the Brazilian Vegetable Oil Industries Association announced its withdrawal from the Soy Moratorium, following political pressure in Mato Grosso, Brazil’s soy-producing powerhouse. Major traders including U.S.-based Cargill, Bunge, and ADM, quickly followed.

The landscape for 2026 is increasingly hazardous for Brazil’s forests and their communities. Alongside grassroots resistance to emboldened destructive actors, the year will be defined by disputes over rules and precedents. In the Amazon, rules determine who is heard, who is protected, and who pays the price of a model of “development” presented as inevitable.

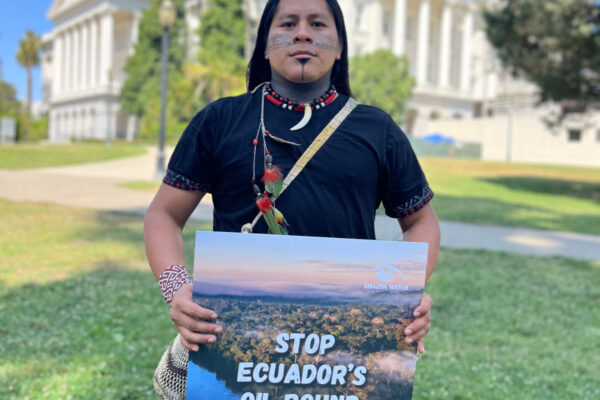

In this context, Amazon Watch’s response will focus on three fronts. First, strengthening the leadership and protection of Indigenous peoples and traditional communities through supporting legal and communications strategies grounded in rights and community-defined protocols. Second, monitoring and challenging decision-making frameworks that seek to fast-track projects, to prevent legal changes from being weaponized against safeguards. Third, increasing international pressure on companies, financiers, and political actors who benefit from deregulation, while linking territorial defense to the global struggle for climate action, rights, and corporate accountability.

As 2026 unfolds through relentless news cycles, we must be prepared to confront injustice on many fronts. As always, we draw strength and inspiration from the enduring struggles of Indigenous peoples, whose determination and leadership remain central to collective resistance.