Indigenous people who protested during the U.N. climate negotiations in Belém, Brazil cited among their main grievances a rail project that would stretch from Mato Grosso to Pará and cut through the Amazon rainforest.

For agribusiness, Ferrogrão, as the railway project is known, would represent a logistical revolution.

Critics see yet another massive infrastructure project that threatens the Amazon and undermines President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s stated commitment to the environment and Indigenous rights.

What is the idea behind Ferrogrão?

Brazil is the world’s largest exporter of soy and corn, much of which is produced in Mato Grosso.

Today, that cargo travels long distances by truck to seaports in the south or river ports in the north.

For more than a decade, governments have tried to push forward a 933-kilometer railway that would connect the city of Sinop, in Mato Grosso, to the port of Miritituba, in Pará.

From there, the grains and legumes would reach the Amazon River and the Atlantic Ocean.

What do supporters of the project say?

Elisangela Pereira Lopes, technical adviser for the Brazilian Confederation of Agriculture and Livestock (CNA), the country’s main agricultural producers’ organization, told AFP that the railway was “essential to ensure the competitiveness of Brazilian agribusiness.”

Mato Grosso, which accounts for roughly 32 percent of national grain production, “needs a more efficient logistical route to keep up with the sector’s growth,” she emphasized.

Lopes said the railway was expected to reduce logistics costs for grain exports by up to 40 percent, in addition to reducing road traffic and associated carbon emissions.

What do critics say?

Mariel Nakane, of the Instituto Socioambiental (ISA), told AFP that the railway would affect Indigenous lands and fuel deforestation and territorial encroachment.

She added that agribusiness’s shift over the past decade toward exporting products more cheaply through northern river ports has already transformed the Tapajós River, where the port of Miritituba is located.

“Riverine communities are being pushed out,” she lamented. “They can no longer fish in some areas, because now it is all port operations and barge traffic. They are run over by the barges.”

Nakane said that construction of Ferrogrão aims to increase by fivefold the volume of goods transported along that route.

The expert fears that a lack of control will prevail in areas already vulnerable to deforestation.

She argued that current licensing procedures are not sufficient to protect the forest and its inhabitants.

Nakane also pointed to other controversial projects, such as oil exploration along the Equatorial Margin – whose exploratory drilling phase has been authorized – near the mouth of the Amazon River, and plans to pave BR-319, a major highway in the rainforest.

“It is very easy for the government to claim it is committed to the climate agenda, but then sweep these controversial projects under the rug,” she said.

Why did this come up during COP30?

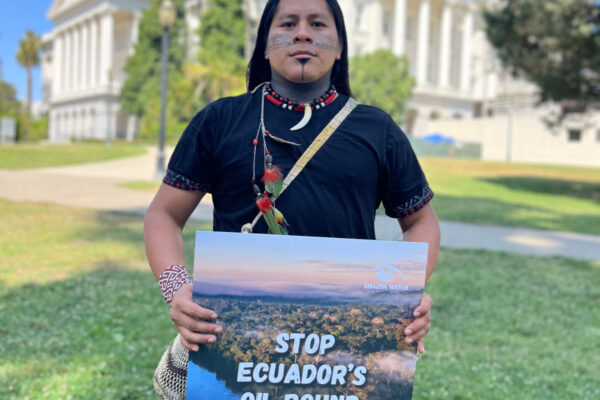

With the world’s attention focused on Belém, where COP30 is taking place to address climate change, Indigenous communities sought to draw attention to their demands, including a ban on Ferrogrão.

Protesters are also furious about a decree signed by Lula in August that designates the Amazon’s major rivers, including the Tapajós, as priorities for cargo navigation and private port expansion.

“We are not going to allow it, because this is our home, our river, our forest,” said Indigenous leader Alessandra Korap, of the Munduruku people.

“The river is the mother of the fish.”

Where does the project stand now?

Brazil’s environmental agency, Ibama, said in a statement to AFP that “the licensing process for Ferrogrão is in its initial stage, with evaluation of its environmental feasibility.”

That process was suspended in 2021 by Federal Supreme Court (STF) Justice Alexandre de Moraes, the case’s rapporteur, while the court considered a constitutional challenge to plans to change the boundaries of Jamanxim National Park in Pará to allow construction of the railway.

Moraes allowed the case to resume in 2023, and the court began reviewing it again last month. The rapporteur voted in favor of allowing the project to move forward.

However, the hearing is currently on hold after Justice Flávio Dino requested more time to analyze the case.