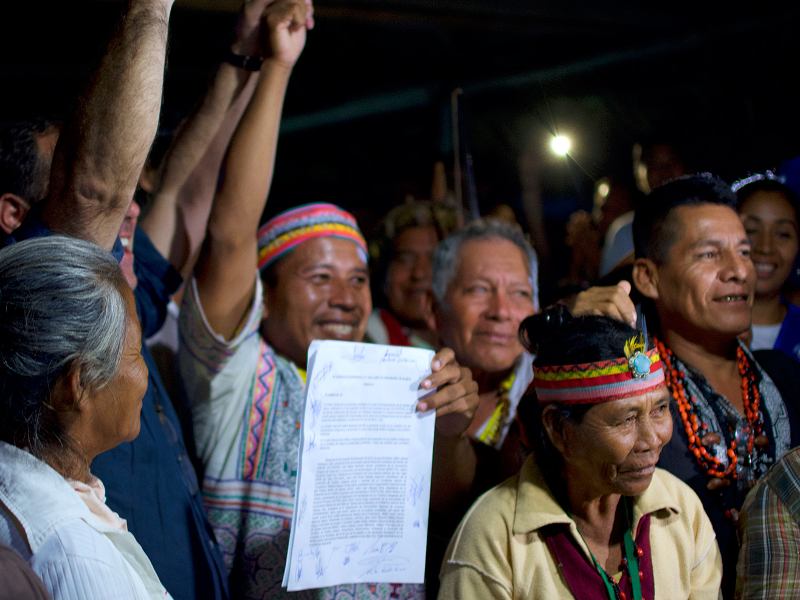

Could the recent mobilization held at Saramurillo in the northern Peruvian Amazon be remembered as the one that finally brought much needed justice to indigenous peoples affected by over 40 years of irresponsible oil activity? In mid-December 2016, 49 agreements were signed between Peruvian government officials and indigenous peoples. Will things be different this time; will the accords be complied with? In the wake of too many state promises left unfulfilled and the constant oil spills on their territories, hopes are nevertheless high for the thousands of native peoples who united during 117 days in the native community of Saramurillo to demand respect for their rights and to call for an end to the oil destruction of the Peruvian Amazon.

Coming from five river basins of the Marañón, Corrientes, Pastaza, Tigre, and Chambira, this broad coalition at Saramurillo was formed by different Amazonian peoples such as the Kukama, Urarinas, Achuar, Kichwa, and Quechua. Approximately 3,000 people were present at the peak of the protest. All have suffered the impacts of pollution on their territories owing to Peru’s two oldest Amazonian oil fields and pipeline.

The agreements concluded this three-and-a-half-month long protest, which began on September 1st 2016. Indigenous peoples sustained a blockade of a section of the Marañón river as a means to press for their demands until November 29th. After several failed attempts at dialogue, and instead of militarizing the conflict, the Peruvian government responded this time by renewing the dialogue on-site in Saramurillo with a state commission headed consecutively by Minister of Justice and Human Rights Marisol Pérez Tello, Minister of Energy and Mining Gonzalo Tamayo, and Minister of Production Bruno Giuffra in December 2016. “The main problem here is employment,” affirmed Peru’s Minister of Energy and Mining. “Tell me, indigenous leaders, who among you haven’t been working for the oil companies?” Hundreds of people gathered at the traditionally-built community center stared at him in silence.

Our Executive Director and legal counselor to the indigenous people, Sarah Kerremans, testifies: “I almost fell off my chair when hearing the Minister’s opening words to hundreds of indigenous fathers and mothers with exhausted yet hopeful hearts and minds after 117 days of pacific protest. One Achuar leader stood up to break the silence, he was very gentle when he spoke: “We know you duty holders from Lima have difficulties to understand what we really mean, but don’t worry, we will not get tired of explaining our legitimate demands, not even if we have to do so for several days, over and over again. It will necessarily be an intercultural debate”. It was a strong statement that set out the rules for this long debate, which resulted in 49 signed agreements.”

The Peruvian region of Loreto – a micro Venezuela, whose local economy has depended upon oil for the past four decades – entered a severe economic crisis in 2015 when the international oil price per barrel dropped. Yet the indigenous peoples’ first demands at Saramurillo were not about jobs. Sarah, a fundamental rights specialist who has been involved in numerous dialogues, roundtables and prior consultation processes between indigenous peoples and the Peruvian state over the last three years, sees a trend: “This is part of a broader strategy. First of all, the Peruvian state has not been a guarantor for fundamental rights in Loreto for a long time. When indigenous peoples claim their rights after four decades of oil activity on their ancestral lands – fundamental rights such as the right to clean water, their territories, and the right to life itself – they are not listened to. There seems to be a tendency to use the idea of jobs creation, or even the so called “empresas comunales” to meet these demands. This might work for a while and does give the impression of direct satisfaction and immediate attention in places where there was little attention before. But after a while, community members see that the problem remains the same over the long term. So one of the main issues put on the table in Saramurillo was not about employment, but rather the immediate and effective remediation of the thousands of contaminated sites in oil Block 192 (operator: Pacific Stratus Energy, former operator Pluspetrol), oil Block 8 (current operator: PlusPetrol) and along the 800 km long pipelines (operator: Petroperu) which cross the Amazon.”