More than 24,000 hectares of land occupied by three native communities in the Huanuco region are being taken over by invaders as runways used for drug trafficking and coca fields increase on their lands. The Kakataibos of Unipacuyacu have been displaced by drug trafficking in less than one percent of their territory. In Nueva Alianza, the large-scale illegal land titling of individual properties reduced to half the area that the Shipibos have been seeking to title for the past 20 years. Nueva Austria del Sira lost almost 2,000 hectares of forest. The incursion of loggers and land traffickers has both Yáneshas and Asháninkas under threat. A Convoca.pe team traveled through part of the territory occupied by these ethnic groups that are considered among the most representative of the Peruvian Amazon, and this is what the team found.

Unipacuyacu: living under seige

The roar of chainsaws is getting closer and closer, but Anselmo, a sturdy hunter with a leisurely gait, knows which route to take. He leads us along a path that, due to the force of footsteps, has formed on the grass, meanders through thickets, and penetrates the forest. On both sides, the rainforest gradually envelops the road and makes it imperceptible. At times it is a row of fallen leaves in the undergrowth; and at others, a rough path cut by streams or elevations. When the forest becomes denser, Anselmo cuts the entwined branches with a machete, pulls out vines, and clears the path. The tops of the quinilla and shiringa trees still form a blanket that protects you from the sun in this part of the central Peruvian rainforest. By reflex, the hunter stops suddenly under the tree trunks if he suspects that a sound is not coming from the movement of birds or iguanas. Therefore, we have to do the same. We are now in a high-risk area: coca growers, loggers, and drug traffickers often travel the same tangled path.

“Up ahead,” whispers Anselmo, “this whole scene of trees will change.”

It has been two hours since we left the local communal space of the Unipacuyacu native community in the Huanuco region. This is just a sector of the vast forest that the community has been losing with the constant presence of invaders. It was not just a hunting territory for the local Indigenous people, and an unlimited pantry of food and materials to make their homes, but also sacred space for the conservation of imposing lupuna and shihuahuaco trees, which are more than 200 years old and 60 meters high.

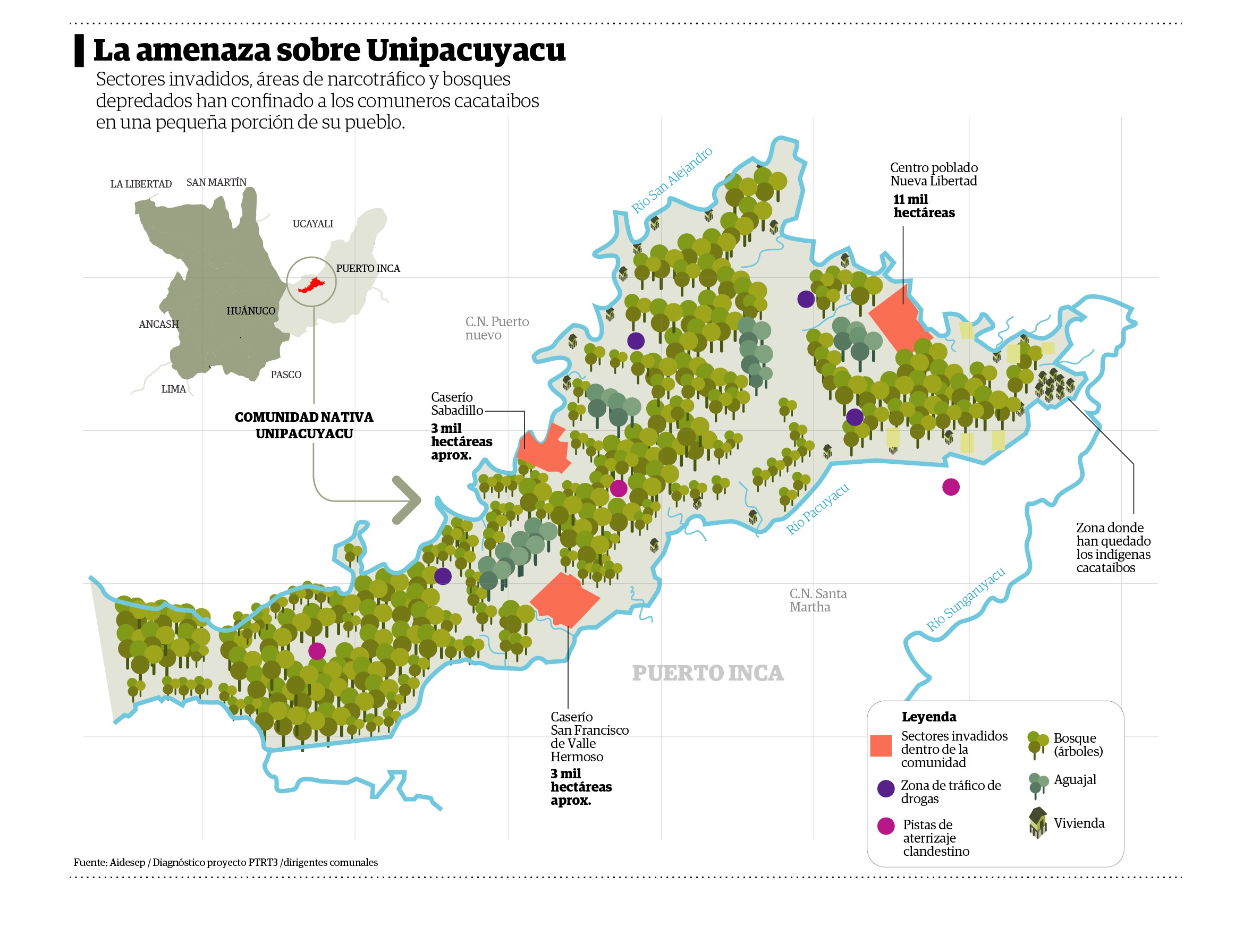

Unipacuyacu is located in the district of Codo del Pozuzo, the province of Puerto Inca, on the eastern side of Huanuco, forming a triple border with Ucayali and Pasco. To get there you must first travel four hours by car from Pucallpa, the capital city of Ucayali, to the rural community of Nuevo San Alejandro, a route that unveils wide tracts of smoldering land and fallen trunks that not so long ago were once bolaina trees. The final stretch to the native community is along the Sungaruyacu River.

Alcides, a short man who grows yucca, says that crossing the forest these days depends more on luck than the weather. He is at the end of the short line led by Anselmo, but he will be the first to cross the stream that separates the dense rainforest from the first coca field along the route.

There are at least six hectares of crops comprising a farm surrounded by hills also covered with coca. Harvest time still seems far away. There are no coca growers in the area. We must move quickly, but quietly, and always on the side traced by the stream. From an elevation that sets the boundary of a large lot of land, smaller, contiguous smallholdings come into view. A few sunken tree trunks among the plantations are the only signs of the previous logging. “This is what our forest is becoming,” said Alcides, with arms wide open, “this is the land of invaders.” What has happened here, the hunter explains, is that everything has been destroyed by men with chainsaws who operate throughout the year. They are the ones who make themselves heard along the route, and who must be avoided.

The Indigenous people of Unipacuyacu live cornered in their own territory. Coca cultivation and the threat of drug trafficking are expanding in areas that have been invaded and illegally recognized by the authorities. There are clandestine drug laboratories and runways for the departure of flights transporting cocaine. The community members have lost almost 17,000 hectares of their land to invaders. This situation is repeated in the native communities of Nueva Alianza and Nueva Austria del Sira, where 7,000 hectares have been illegitimately titled. In summary, more than 24,000 hectares of these native communities are now foreign to their original inhabitants.

A besieged village

The native community of Unipacuyacu is surrounded by the Pacuyacu stream and the San Alejandro and Sungaruyacu rivers. There are no more than 20 houses made from wood and branches, scattered between cassava or cocoa cultivations, on about five hectares of land. The village is home to 43 Kakataibo and Shipibo Indigenous families. There are also some Yáneshas.

“Those of us who have stayed behind are here in retreat,” says community leader Marcelino Tangoa, a 46-year-old Shipibo who recently assumed the position.

Unipacuyacu is one of the 631 native communities in Peru that still do not have a title deed, according to the registry of the Ombudsman’s Office of Peru. In 1979, Kakataibo natives who controlled the river basins located between Puerto Inca (Huánuco) and Aguaytía (Ucayali) assumed ownership of this territory. After 16 years, on December 19, 1995, the Ministry of Agriculture recognized Unipacuyacu by means of a board resolution. The following year, the community members managed to demarcate the 22,946 hectares where they grew their traditional cultivation (cassava, corn, or rice), fished, and harvested. Since then, all of the community’s leadership has been engaged in a never-ending struggle to achieve titling. Meanwhile, groups of invaders have been taking control of a sector within Unipacuyacu. The Municipalidad Provincial de Puerto Inca illegally created a village there, resulting in the formation of two hamlets. The community members can currently no longer access these sites.

Farmers from Ayacucho and Tocache (San Martin), recalls the former leader, were taking over large sectors of the community for their sowing. At that time, the Indigenous people were not clear about how much space they were losing, nor what new cultivations were expanding on their land. On July 16, 2008, only two years after the invasion began, the Municipalidad Provincial de Puerto Inca recognized Nueva Libertad as a village. The design brief for this site established an area of 11,005 hectares. A resolution of the Mayor’s Office was issued when Unipacuyacu’s leadership was struggling for more than a decade to obtain its legal certainty.

Ermeto Tuesta, a specialist in geographic information systems and titling of Indigenous communities at the Instituto del Bien Común – IBC (Common Good Institute), explained in this Convoca.pe report that municipalities validate the existence of a village through acknowledgment as part of their jurisdiction. “The acknowledgment of local governments,” says Tuesta, “does not grant property rights.” However, Marcelino, the community leader, says that the invaders of Nueva Libertad operate as owners of the land recognized for Unipacuyacu.

Two years after the acknowledgment of Nueva Libertad, part of its population moved toward the Sabadillo and Batuan streams. There the hamlets of Sabadillo and San Francisco de Valle Hermoso were formed. Each one covers almost 3,000 hectares within Unipacuyacu.

According to several testimonies collected in the community, there was pressure from civil servants against several Indigenous leaders to make them accept the handover of their communal lands to the settlers. The Federación de Comunidades Nativas de Puerto Inca y Afluentes – Feconapia (Federation of Native Communities of Puerto Inca and Tributaries) details in a memorial that this occurred, for example, during a meeting held on November 7, 2019. The accusation is against Adolfo Cachay, the attorney at that time of the Dirección Regional de Agricultura – DRA (Regional Directorate of Agriculture) of the Gobierno Regional de Huánuco (Regional Government of Huanuco). It is alleged that he coerced the Indigenous representatives in order to “avoid territorial conflicts” in a meeting called a “coordination about the illegal transfer of rural lands and creation of villages.” Feconapia describes that the session was also attended by invaders and coca growers.

The type of soil and the warm weather, similar to that of Vraem, as well as the absence of controlling agencies and the complicated geography when crossing the forest to the devastated areas where coca bushes now proliferate, make this community a strategic location for the illegal coca cultivation. Anselmo is not a Kakataibo or Asháninka from Unipacuyacu, but he has made the trek so many times that he could do it even at night. He lifts the wire fence that, according to the warning made to the Indigenous people, marks the beginning of Nueva Libertad. He points out the route along which he has arrived and announces: “You will see more than entire coca fields.”

Hotspot for drug trafficking

There is a path that goes into the forest from one side of the six hectares of coca fields where we are now. About 300 meters along the path, two maceration pits are found: the enormous pits where the coca leaf is transformed into drugs. In a hut made of plastic, there are still the tools and containers for chemicals that were used to process the most recent harvests. Toxic waste from this camp reaches the San Alejandro River, which becomes the Sungaruyacu and feeds the Pacuyacu. In other words, the water that the Unipacuyacu community members use to live is contaminated from here, the water that is making them sick. Alcides and Anselmo say that this is just one of the bases for drug trafficking in the native community. They are not sure how many more there are, but they know that the chemicals have almost killed off butterfishes, sabalos or pacus, which are fish that the Kakataibos and Shipibos of the village used to consume.

Nearby, almost on the border with Santa Martha, another Indigenous Kakataibo community, there is a clandestine runway from which drug planes take off up to three times a week. This is how Alcides has estimated it since he spends every afternoon in their cassava fields. He says that it is not the only runway; there are others in Sabalillo.

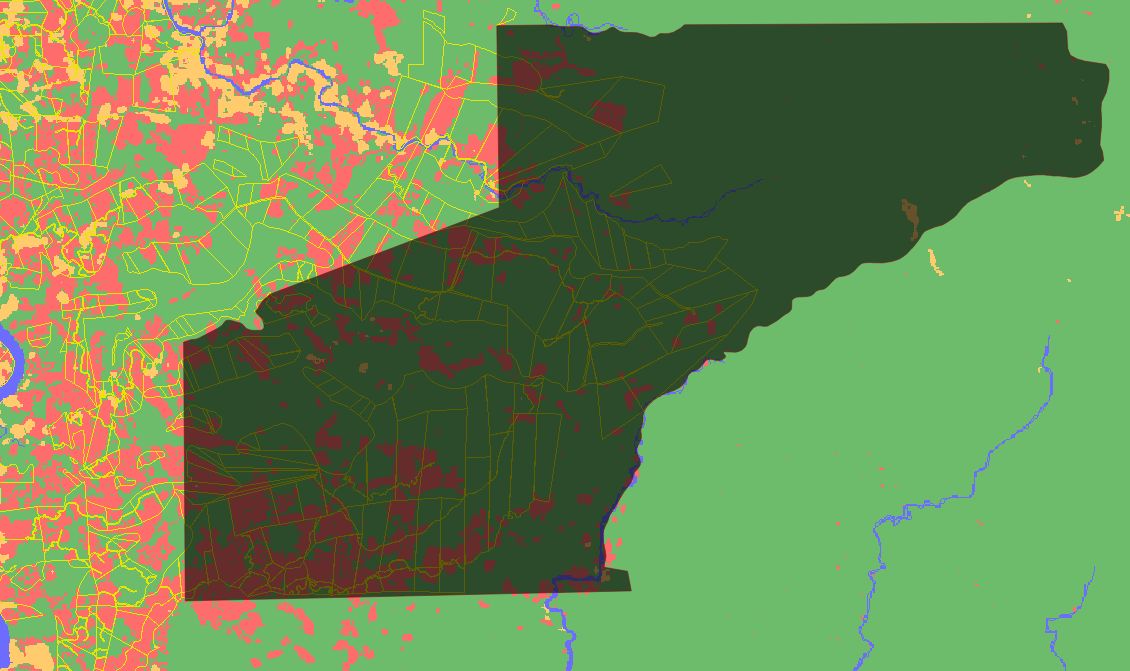

Convoca.pe analyzed the information contained on the Geobosques platform of the Ministerio del Ambiente (Ministry of Environment) and from the Unipacuyacu area in the Sistema Catastral para Predios Rurales – SICAR (Cadastral System for Rural Properties) of the Ministerio de Desarrollo Agrario y Riego – MIDAGRI (Ministry of Agricultural Development and Irrigation). According to this, 6,854 hectares of the native community were deforested between 2001 and 2020. Of the total amount of clearcutting, the highest rates were recorded in 2010 (5,198), when the village and hamlets were already settled. In addition, this source corroborated that there are hotspots for forest degradation within the 11,005 hectares recognized illegally by the municipality of Puerto Inca in Nueva Libertad.

“Titling is a procedure that is extremely onerous and takes years or decades for a native community. This facilitates that amid the communities’ legal uncertainty, other groups are positioning themselves, destroying the Amazon and promoting illegal economies,” explains Mar Perez, head of the Unidad de Protección a Defensores de la Coordinadora Nacional de Derechos Humanos (Coordination Unit for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders) for this report.

Due to the serious problems in their territories, Unipacuyacu and Nueva Alianza, located in the district of Honoria, were the native communities of Huanuco included in the Rural Land Cadastre, Titling, And Registration Project in Peru – Third Phase (PTRT3, by its Spanish acronym) implemented by MIDAGRI with financing from the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB). The PTRT3 aims to title 403 native communities in 10 regions of the country, divided into four lots. Huánuco, Ucayali and Junín are part of Lot 2. Since August 2019, the company SIGT S.A. Ingenieros Consultores, in coordination with the Asociación Interétnica de Desarrollo de la Selva Peruana – AIDESEP (Interethnic Association for the Development of the Peruvian Rainforest), has begun developing socio-environmental diagnoses for the Indigenous peoples considered in the titling project.

The company verified, for example, that within Unipacuyacu, individual titles have not been granted to the settlers of Nueva Libertad and the hamlets of Sabadillo and San Francisco de Valle Hermoso; instead, they have been granted certificates of ownership. According to Aidesep, through the people in charge of carrying out the diagnosis, the sectors created in the native community developed maps of their urban areas along with proposals for rural areas, and with these sketches they intended to be continuously titled. A situation that conflicted with Unipacuyacu’s intention, and as a result paralyzed the community’s formalization process year after year.

By the end of 2019, the struggle undertaken by Arbildo Meléndez, former Kakataibo leader of Unipacuyacu, allowed a brigade of technicians to enter the community to carry out soil surveys as part of the land titling process. During the trip through the invaded areas, two men threatened to shoot at the retinue if they did not desist from their work. The Kakataibos said that despite everything the crew had completed the fieldwork and Arbildo escaped with the technicians through the forest. “The titling file was almost ready, only the new delimitation of the community was missing,” they reported, “but the threats against Arbildo increased”.

At that time, the municipal agent of Nueva Libertad, Miguel Quispe García, sent a series of documents to the Regional Directorate of Agriculture (DRA, by its Spanish acronym) of Huánuco, office in charge of land titling, in order to cancel the procedures by which Unipacuyacu was supposed to achieve its legal certainty. Among the documents, to which Convoca.pe had access, Quispe attached a memorandum wherein he requested that the PTRT3 not carry out works in the area recognized for Nueva Libertad, a list of the 303 properties that comprise the urban area of the village, a map, and a resolution of February 11, 2019, in which he was recognized as a municipal agent by the current mayor of Puerto Inca, Hitler Rivera.

AIDESEP reported for this investigation that the DRA of Huánuco requested to consider the documents sent by the leader of Nueva Libertad and to take into account the settlers’ opposition to Unipacuyacu’s land titling. Technicians reveal that this fact and insecurity in the area for the pending delimitation work stalled the process until the pandemic began. Additionally, a group of settlers threatened the coordinating engineers at their work offices.

Arbildo Meléndez was murdered on April 12, 2020. This was the fourth crime perpetrated against a Unipacuyacu community member. In 2010 Segundo Reátegui was murdered (along with his 4-year-old son); later Manuel Tapullima, a witness of the double homicide, was found drowned. Arbildo’s grandfather, Justo Gonzales, died after being tortured in June 2016. In the Arbildo Meléndez case, the authorities recently ordered the detention of Redy Ibarra Córdova, the apu’s confessed murderer, who in the first instance was released for lack of evidence. He is now a fugitive. The rest of the cases are stalled.

The Common Good Institute (IBC), a civil association that works with rural communities in managing their resources, has documented that eight of the 21 Indigenous people murdered in the Peruvian Amazon since 2010 were from the Kakataibo ethnic group. Four of them were murdered between April 2020 and October 2021. The first crime in this last period was against Arbildo Meléndez. “The Kakataibo communities are the hardest hit by violence in the Peruvian Amazon, and this is mainly due to drug trafficking and illegal logging,” says Álvaro Másquez, a specialist in the area of Constitutional Litigation and Indigenous Peoples at the Instituto de Defensa Legal – IDL (Legal Defense Institute).

The map designed as part of the diagnosis for the Unipacuyacu land titling has estimated a communal area of 20,280 hectares (2,666 hectares less than the area requested by villagers). Within the territory, the existence of four illicit drug trafficking areas, three clandestine runways (one of which is almost on the border with Santa Martha), three illegal logging areas, and two illegal mining areas have been identified. All of them are within the Unipacuyacu area, where the Kakataibos and Shipibos are no longer able to access them due to death threats. The map also includes the village of Nueva Libertad and the hamlets of Sabadillo and San Francisco de Valle Hermoso.

The community leadership has decided not to accept a land titling proposal with “invaders” on it. However, the director of the DRA of Huánuco, Roy Cruz, believes that at this point the only way to reach an agreement is through dialogue between the Indigenous people and the settlers. The other option, Cruz declared for this report, is the beginning of a judicial process that could extend over many years and lead to social conflict. “We have to understand that they are people who have been living in their homes for 10 or 15 years and that they also have crops,” he said.

“But they are all coca crops,” grumbles a former Indigenous leader before boarding his canoe.

“We don’t exist in the eyes of any government.”

He throws the accumulated water from the canoe into the Sungaruyacu River. Then he leaves.

Nueva Alianza: a never-ending struggle

It is September 11th and we are in the native community Nueva Alianza, in the Huanuco region inside the Peruvian rainforest. It is a village with 243 inhabitants that today celebrates its anniversary. It has been 34 years since a group of Shipibo Conibos decided to settle here and give this place the name it bears.

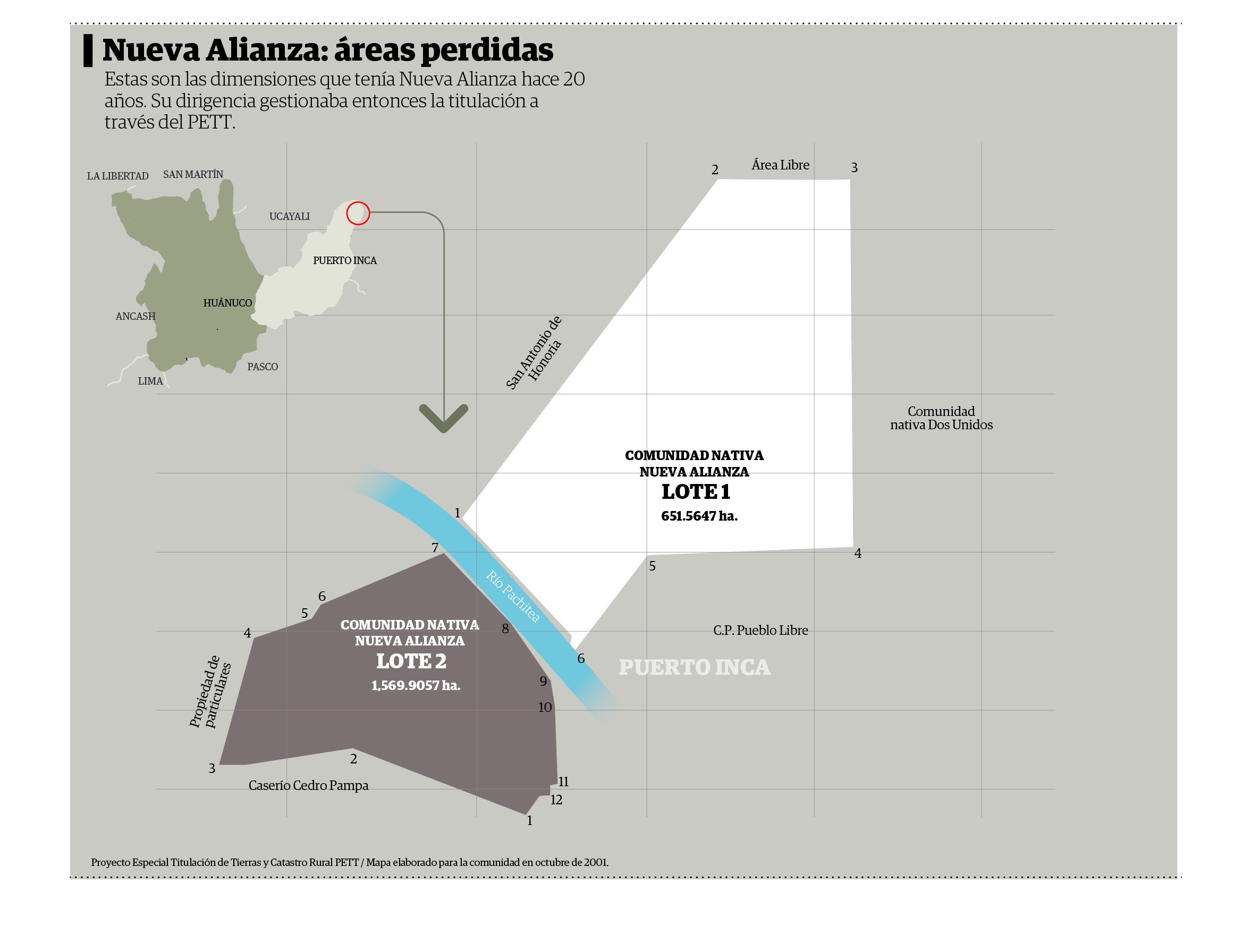

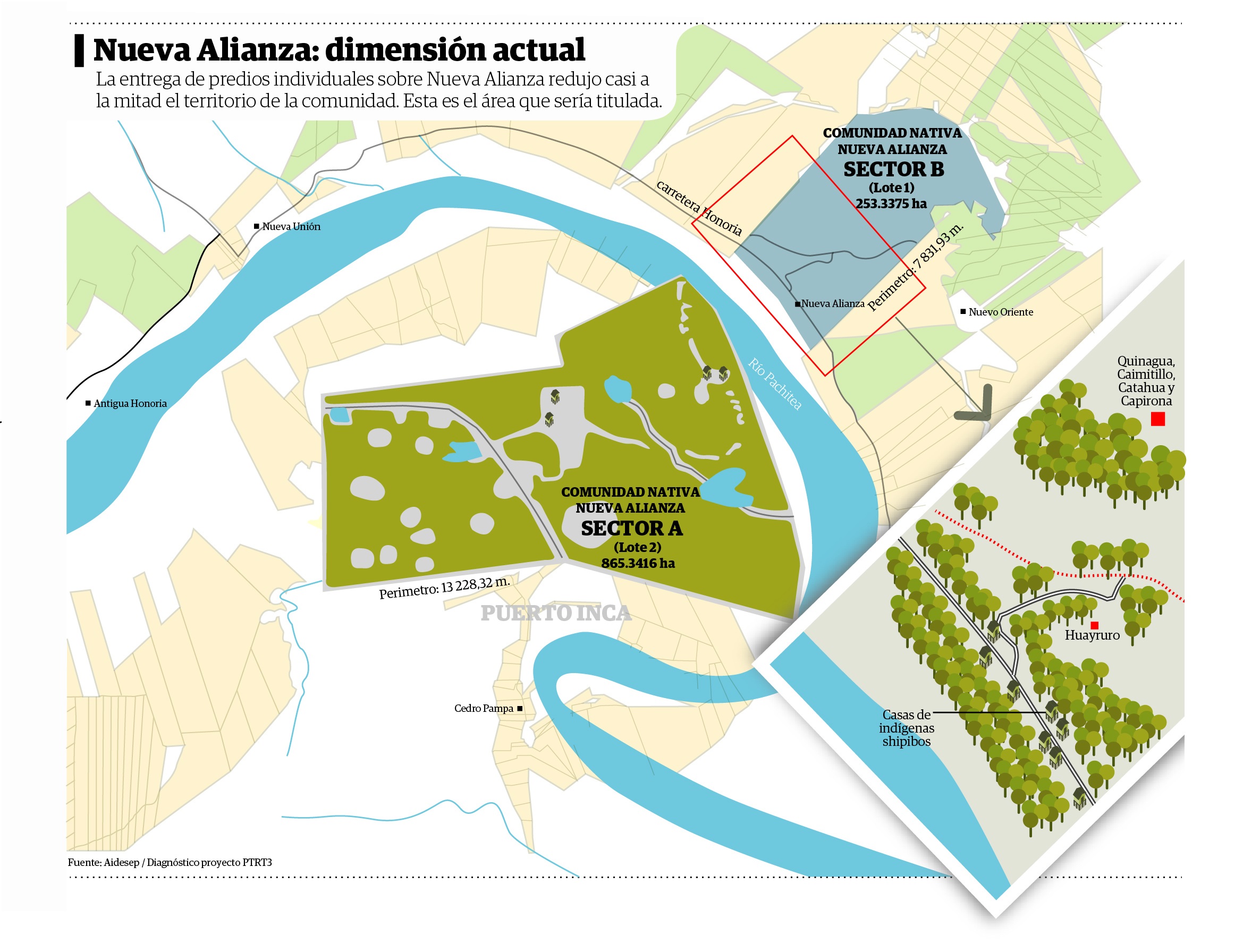

The road that separates the houses of Nueva Alianza in two rows is called Honoria, the same name as the district where the community is located, in the province of Puerto Inca. About 50 meters away you can find the Pachitea River, which cuts Nueva Alianza into two sectors: Lot 1, where the Shipibo people live; and Lot 2, which is mainly a hunting area with cassava and corn crops.

“We celebrate 34 years even though we are still unprotected and vulnerable,” says Santos with a gesture of regret. The community was recognized by the directorial resolution of the Regional Directorate of Agriculture of Huánuco on August 9, 2000, and to date has not been titled. On the contrary, the lack of legal certainty has allowed part of the original Nueva Alianza area to be mutilated and titled in favor of settlers over the last 20 years.

Never-ending process

On the map that the leader evaluates there is a stamp of the Special Land Titling and Cadastre Project (Proyecto Especial de Titulación de Tierras y Catastro Rural – PETT) corresponding to October 2001. At that time, the native community had an area covering 2,220 hectares: 651 hectares in Lot 1 and 1,569 hectares in Lot 2. The PETT was the entity, within the Ministry of Agriculture, in charge of formalizing properties between 1992 and 2007. Afterwards, its functions were assumed by the Agency for the Formalization of Informal Property (Organismo de Formalización de la Propiedad Informal – COFOPRI) within the Ministry of Housing, Construction, and Sanitation (Ministerio de Vivienda, Construcción y Saneamiento). From documentation archived by previous leaders, Santos took out a document labeled as “Map of the Delimitation and Titling of the Communal Territory of the Nueva Alianza Native Community.” The map was issued by COFOPRI in July 2008 and revealed that by that time the Shipibo people had already lost 176 hectares in Lot 1.

All of those graphics are part of a series of blueprints for titling that never came to fruition. Nueva Alianza authorities state that they could have realized that the community was losing territory due to the expansion of an adjacent settlement, if the government had studied the land and drew up maps. During those years, the villagers were still able to move without complications through the forests and small farms with crops on both sides of the village. But since 2015, he details, the massive and violent incursion of men from San Martin, Bagua (Amazonas), and Cajamarca has displaced Shipibo families.

“Our authorities allowed the invaders to enter and establish themselves in the community,” recalls Jocías Inuma, the vice president of the Federation of Native Communities of Puerto Inca (FECONAPIA).

Nueva Alianza is one of the native communities in Huánuco affected by a land titling policy implemented in this region by the Regional Directorate of Agriculture (DRA) between 2013 and 2018. This had its origin in an Inter-institutional Cooperation Agreement between the National Commission for Development and Life without Drugs (Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo y Vida sin Drogas – DEVIDA) and the Regional Government of Huanuco signed in December 2012. During the period when the land titling was carried out (2013-2018), DEVIDA allocated US$4,000,319 (S/13,445,075), as it was an initiative that promoted sustainable economic activities as part of the solutions against illegal crops. DEVIDA dispursed the funds through the Budgetary Program of Alternative, Integral, and Sustainable Development (Programa Presupuestal de Desarrollo Alternativo Integral y Sostenible – PIRDAIS), which had among its activities the Rural Land Formalization and Titling project.

According to the official document explaining how the PIRDAIS had to be implemented and what DEVIDA reported to the Congress of the Republic of Peru, this project included the land titling of individual rural properties and those of native communities. However, during its development, only individual land titling was prioritized. No land titles for Indigenous people were formalized.

The Common Good Institute argues that contrary to the plan, a “strategy of settlement and invasion from the State’s own institutions” was undertaken. Dozens of individual land titles were granted by the DRA of Huánuco over native community territories. In Nueva Alianza, the first titleholders were rice growers from the San Martín region, and then groups of coca growers who began to roam the forest and took over the old community center, report former leaders. Little by little, most of Lot 1 territory in the community became impassable land for the community members. Today, the Shipibos cannot go very far due to the small farms near the houses along the road.

“We lived under threat. We had to plant our crops in this area. We are still afraid,” says Santos, standing on the banks of the Pachitea River. Then he points to the other bank, the one belonging to Sector 2. “There used to be houses there, but that side floods frequently.”

The Regional Directorate of Agriculture of Huánuco issued 15,038 individual land titles during the period (2013-2018) in which DEVIDA financed the process, according to information provided by this organization to the NGO Proética in July last year. Details are shown in a table entitled “Land Titles Issued by Year and Geographic Area.”

In Puerto Inca, the province where the Nueva Alianza community is located, individual land titles were granted from 2015 to 2017, amounting to 3,571. Convoca.pe repeatedly requested an interview with DEVIDA civil servants to obtain information regarding the funds and the number of land titles granted, but at the close of this report we have received no response.

However, in a note issued by the organization in November 2017, it is indicated that the aim for that year was 1,200 land titles. And in another, published in January 2019, DEVIDA reports that this had indeed occurred. That year, the amount disbursed was US$246,761 (S/800,000), one of the lowest while the project lasted. The highest amount reached US$1,479,727 (S/5,000,000) used for granting 5,200 land titles during 2015. Roy Cruz, director of the DRA of Huanuco, explains that from the office he heads today, the number of land titles to be granted per year was set, and based on this funding was requested from DEVIDA. “It had to be complied,” he notes, “otherwise DEVIDA would not provide resources the following year.”

One of the questions posed to DEVIDA in this investigation was if they carried out any verification process after the land titles were granted. The institution did not respond to the requests for interviews, but in mid-March, in communication with the Peruvian TV program Cuarto Poder, the regional manager of DEVIDA-Pucallpa, Laura Mantilla, said that the financing for land titling was carried out within the framework of the technical proposals for intervention presented by the “subnational governments.”

“They have to take care, to be vigilant of the areas that have to be registered,” she stated.

Taken land

In the case of Nueva Alianza, through an evaluation in the Land Recording System for Rural Properties, Convoca.pe found that to date there are more than 110 titled properties in the area, previously established by the community in October 2001. These are lots of up to 45 hectares that in several cases belong to the same owner. In the total area corresponding to Lot 1 (651 hectares) of the community, there are 98 overlapping properties covering approximately 398 hectares. An analysis of satellite imagery carried out by this investigation showed that there is deforestation on almost all the land titled.

The sector of Lot 1 where the properties were granted was called Nuevo Oriente by its inhabitants. It takes about 10 minutes by pick-up truck from the highway where the houses of Nueva Alianza are located to get to Nuevo Oriente. However, it is a stretch that the community members prefer not to pass through for security reasons. They know that more and more illegal loggers and coca growers linked to drug trafficking operate in these forests. In contrast to the area occupied by the Shipibos, in Nuevo Oriente, there is a school in good condition, some decent infrastructure construction, and two-story houses. Additionally, there are also deforested areas where recently, according to truckers, there was prolific logging of timber trees.

The irregular actions of the DRA of Huanuco was a significant factor that halted and slowed down, land titles to a rural community that had been requesting this benefit for more than 15 years. The case of the Shipibo Conibo people is a small-scale reality of the harsh situation of several communities in Puerto Inca. The director of the DRA attributes this to the irresponsible behavior of the technicians who worked there and were supposed to go out into the field to perform the verifications during the period in which the government agency disbursed the funds.

“There were many mistakes. They worked for the sake of it in 2013, 2014, until 2017, in the cabinet,” Roy Cruz indicates. “They did not go out to the places where there was overlapping, they did not make the proper diagnosis to initiate a massive land titling.”

Among the few answers it has given on this issue, DEVIDA stated to the former congresswoman of the Commission of Andean, Amazonian and Afro-Peruvian Peoples, Katia Gilvonio, that the DRA of Huanuco is the office with the functional capacity to attend to claims regarding the land titling process. In addition, in a statement issued in February 2021, the organization pointed out that for more than three years it has stopped financing interventions for land titling, and that the execution of this activity was now entirely the responsibility of the local authorities that request the funds.

“There is a causal relationship among the granting of land titles, the positioning of the settlers, and the increase in deforestation. The impact of this policy for individual land titling on Indigenous communities is truly devastating,” says Mar Pérez, from the National Coordinator for Human Rights (Coordinadora Nacional de Derechos Humanos). The attorney believes there was negligence by DEVIDA, which, in her opinion, the organization ratifies by stating that “it has no obligation to supervise what the regional governments do with the funds that were given to them.”

In her opinion, the different sources of international cooperation that were financing DEVIDA should request an audit to know how the land titling processes were carried out.

String of pressures

An ink-stained sheet in the minutes’ book of the native community indicates that Nueva Alianza and Nuevo Oriente once agreed to “put an end to their problems and live together.” It is a boundary agreement signed on August 29th, 2016, between the leaders of both sectors and engineer Michel Rivera Mallma. The document bears the signatures of 20 people who attended what was called “an opportune and historic moment” by Felipe Díaz Más, who was at the time lieutenant governor of the settlement. Limits and the commitment to respect them were established there. What Santos remembers most about that meeting is the fear that stunned the community members. Shipibo families had been harassed in the previous months when the settlement of outsiders increased, and the community insisted on the land titling process.

“We were forced to sign,” says Santos. “Many already had their lots to request the land titles. Now several of them are no longer there, they sold their lots.”

The result of this string of pressures for Nueva Alianza is that the most recent delimitation of its boundaries, the one carried out by the technicians of the Rural Land Recording, Titling, and Registration Project in Peru – Third Phase (PTRT3), includes 1,118 hectares. This is almost half of the area that the native community had defined in its land titling process 20 years ago. From the new delimited area of 1,118 hectares, 865 hectares belong to Lot 2 and 253 to Lot 1.

According to the map prepared by the technicians responsible for the land titling project, Lot 1 is the area where individual land titles have not been granted. This is not the case with Lot 2. Even though most of this area remained free of individual land titles, 11 overlapping lots occupy a total of 95 hectares.

Unlike Unipacuyacu, Nueva Alianza completed a fundamental step towards formalization by delimiting its boundaries. However, the start of the second stage of Lot 2 of the PTRT3, which includes the land titling phase, has been paralyzed since February 13th, 2021. The one-year extension to complete the project began on that date. Only three months remain until that deadline. In a letter sent to the Presidency of the Council of Ministers (Presidencia del Consejo de Ministros), the Interethnic Association for the Development of the Peruvian Rainforest (AIDESEP) reported that the executing entity of MIDAGRI responsible for the project has not signed the restart of operations “due to negligence and incompetence.”

There is a strange combination of insecurity and resignation among the community members. They say that they are going to promote the land titling of the 1,118 hectares defined, that it is urgent and that they need it soon.

“This is all we can do. We can’t lose any more.” This is the phrase that they often repeat.

Nueva Austria del Sira: forest of threats

“Are you related to Mr. Polico?” I was asked.

“No, I don’t know him,” I replied.

“Really? We own everything,” they started shouting.

María’s forehead was frozen by the barrel of a shotgun similar to the one her father, a Yáneshas like her, used to hunt collared peccaries in the forest. Three men had intercepted her on the side of the road she took to go from her corn farm to the house of Polico Díaz, the leader of the native community Nueva Austria del Sira, in Huánuco. One aimed at her, demanding her to answer or else he would kill her. The other two bombarded her with questions about the apu’s movements: what time he arrived, what paperwork he did, where he went when he was not in the village. None of them believed that she had never seen him, or that she was just a visitor, as she insisted, making excuses and begging for her life.

“‘We are the owners because Nueva Austria doesn’t exist,’ they kept repeating until they left,” Maria recalls with a trembling voice.

Roots of the scourge

For this village that was the scene of tenacious Austrians in search of gold, hence its name, the conflict that is depleting it, began in its southern border with the native community Nuevo Unidos de Tahuantinsuyo. A former community leader, who also fled from Nueva Austria del Sira and must change his residence from time to time for safety reasons, told us for this report that groups of settlers took possession of part of the sector adjacent to both communities and formed the Paujil village. Those who settled there, he said, were only interested in timber exploitation in the area, since they began to uncontrollably deplete the forests on the side leading to Nueva Austria del Sira.

In June 2004, Nueva Austria was recognized as a native community by the directorial resolution of the Regional Directorate of Agriculture of Huánuco. The former leader reports that the ancestral area defined for the land titling of the native community was 13,184 hectares. In the bordering sectors, he specifies, reference points had already been located for the next delimitation of the communal area. However, the process was postponed and stopped for almost 10 years. During this delay, the inhabitants of Paujil, Peter Gómez Yulgo, and Alexander Hernani Serrano requested the Mixed Court of Puerto Inca (Juzgado Mixto de Puerto Inca) annul the resolution of recognition of Nueva Austria del Sira because, according to their allegations, it did not exist. The judicial office, then in charge of Judge William del Aguila Pezo, sent an official letter to the Regional Directorate of Agriculture of Huanuco to carry out an inspection procedure. Óscar Rivas Ascanio, an engineer who specialized in physical and legal diagnosis, carried out the inspection on May 15, 2014, and seven days later issued a report with the results of his visit.

In the document, to which Convoca.pe had access, the engineer stated that the rural community of Paujil had an urban area of approximately 12 hectares on the territory of Nueva Austria del Sira. In addition, he witnessed the community’s forests logged by the inhabitants of the village, and he even went to where the Indigenous families, their homes, crops, and the community center were located. In other words, there was not only evidence of the invasion and the loss of forest cover caused by this, but also the presence of an organized native community. Despite all this, the Mixed Court of Puerto Inca declared null the resolution of recognition of Nueva Austria del Sira, and two years later in April 2016 the DRA of Huánuco definitively abolished the recognition.

During the first demands and negotiations to compensate the resolution of recognition, the community leadership obtained a list of 288 requests for individual land titles to the territory of Nueva Austria addressed to the DRA of Huánuco. According to the villagers, the forest destruction and the settlement of outsiders began to extend from the border with Paujil to different sectors in the Indigenous community. An intervention promoted by the Union of Asháninkas and Yáneshas Nationalities (Unión de Nacionalidades Asháninkas y Yáneshas – UNAY) in October 2017 verified that up to that time the DRA of Huánuco had granted 104 individual land titles out of the 288 requested that were on file after the annulment of the recognition. All of the granted properties were in the community area and belonged to 47 people. The field evaluation showed that most of the title holders had four or five lots. According to the verification report, some of them did not even know the location of all of their lots.

Through an evaluation in the Land Recording System for Rural Properties, Convoca.pe identified that there are now approximately 165 titled lands on the territory claimed by Nueva Austria del Sira. There are more than 5,730 hectares of individually titled lands within the 13,184 hectares of the community. In several cases, the lands granted exceed 100 hectares. There are owners who hold four or five properties, and several of them are family members. One piece of land of more than 169 hectares, for example, is titled on behalf of Peter Gómez Yulgo, one of the inhabitants of the Paujil village, who requested the annulment of the recognition of Nueva Austria del Sira. Community leaders say that many of those who received the land are people from Paujil who were already invading, and also relatives of former authorities of the Municipio Provincial de Puerto Inca.

Since 2016, most of the land titles were granted by the DRA of Huánuco, after the resolution of recognition of the community was voided. 2016 was the fourth year of the Rural Land Formalization and Titling Project for which DEVIDA allocated more than US$4,000,319 (S/13,445,075) to the DRA of Huánuco. This process, reported by DEVIDA to the Congress of the Republic of Peru, contemplated the formalization of native communities. However, it was focused on the legalization of individual properties until it ceased to be executed in 2018.

The National Coordinator for Human Rights states that one of the basic requirements for any person in the framework of these land titling processes is to have previous economic activity in the area where they are seeking to settle. In Nueva Austria, however, the land titles were for people who did not even know the land they were granted. In addition, the leaders and community members point out that they were never called to be part of a neighboring agreement with the beneficiaries.

Related crimes

Facing Polico Díaz’s small farms there is an apocalyptic landscape. Parts of dead trees that, in its most optimistic calculations, must border around 70 hectares in this sector. The apu knew that logging was spreading like cancer through remote areas of the village. He witnessed it with helplessness but also as a disease that could be contained by the authorities. Now he only has to take a short walk from his house in any direction to witness the progressive extinction of trees. “No one is coming here,” he regrets. “It all depends on our own resistance.” By the end of August 2021, the slashing and burning of trees reached the crops of Alejandro, an Asháninka who, without thinking, decided to confront the loggers. They pointed a gun at him, hit his head, and left him with a blunt warning: “Leave or we will destroy your houses with all of you inside.”

It was the closest the invaders came to the communal houses. They are land traffickers who identify areas of the village where there are no individual land titles, so they can control them and then sell them as logging areas or for coca plantations. This is the modus operandi that has been observed and understood by the Indigenous people, especially during the last five years of this scourge. In the part of the native community where the Yáneshas and Asháninkas live, there are still no coca plantations, but logging is alarming. Nueva Austria del Sira has registered deforestation of 1,864 hectares in the last 20 years, according to the Geobosques platform of the Ministry of Environment. The major period of logging in the native community was between 2014 and 2016 totaling 669 hectares, during the years in which its recognition was annulled and the overlapping of individual properties progressed.

An analysis of satellite imagery of the territory of Nueva Austria del Sira, carried out by Convoca.pe, revealed that the deforestation hotspots are over most of the titled lands. What happened on August 21, 2019, illustrates this situation well. On that day, according to what was documented by the Second Corporate Provincial Prosecutor’s Office Specialized in Environmental Matters of Ucayali (Segunda Fiscalía Provincial Corporativa Especializada en Materia Ambiental de Ucayali), the police found six hectares, belonging to the native community, completely logged. The authorities geo-referenced the area and recorded the coordinates. The alert had been issued by community members who accused four people led by Clementino Ponce Condor, a neighbor of the Paujil village. This investigation identified that the established coordinates place the logging area within a 112-hectare property titled by the DRA of Huanuco. This piece of land, as a matter of fact, is in the name of Ponce Condor. However, it is not the only property obtained by Ponce in Nueva Austria del Sira. He is accused of destroying six hectares of forest, and he also has a land title of 11 hectares in his name with clear evidence of deforestation.

Troubled land

In Nueva Austria del Sira, death haunted the community members during 2019. On July 29, 2019, two hitmen attempted to murder the then-apu Germán López, but they mistakenly shot his brother-in-law. The attack was the culmination of a string of threats and surveillance against López for promoting the land titling of his native community. Two months later, Polico Diaz and three community members were supposed to pick him up at the Quimpichari settlement, a delegation from the DRA of Huanuco that had agreed to carry out a socioeconomic study in Nueva Austria del Sira for the processing of new recognition. The inspection was never carried out because, as he shares, he was held by some 30 men for three days in the forest.

So far, not even a team from the DRA or DEVIDA has conducted a comprehensive review in Nueva Austria del Sira to verify if the beneficiaries are carrying out sustainable economic activities as stated in the formalization program in force between 2013 and 2018. The native community has not been included in the Land Recording, Titling, and Registration of Rural Lands in Peru’s Third Stage Project (PTRT3) due to the annulment of its recognition. AIDESEP’s National Territory Coordinator, Waldir Eulogio Azaña, reported that the resolutions of recognition and annulment have suspiciously disappeared from the systems of the DRA of Huánuco, and therefore it is impossible to initiate another land titling process for this native community. Meanwhile, the Common Good Institute estimates that Nueva Austria has 75% of its territory with single overlapping properties and lots negotiated by land traffickers.

Maria, the Yánesha who was about to be murdered, goes back through her memories for one more moment during the last day she spent in her village. Suddenly, she has a brief feeling of distress.

“Do you know what sometimes goes on in my mind?” she asks as if talking to herself.

“We are going to spend our lives on this struggle.”

Co-written with Alexander Lavilla.

This Convoca.pe investigation was carried out in collaboration with the specialized professionals of the Amazon Watch organization.

Credits: Research: Enrique Vera. Data analysis and satellite maps: Alexander Lavilla. Main map visualization: Víctor Anaya. Computer graphics: Iván Palomino. General editing: Milagros Salazar Herrera.