Development projects in the Amazon Basin – including dams, roads, and oil and gas operations – are encroaching on forests that are the last refuges of thousands of indigenous people who continue to shun contact with the outside world, according to a study that estimates the tribes’ locations.

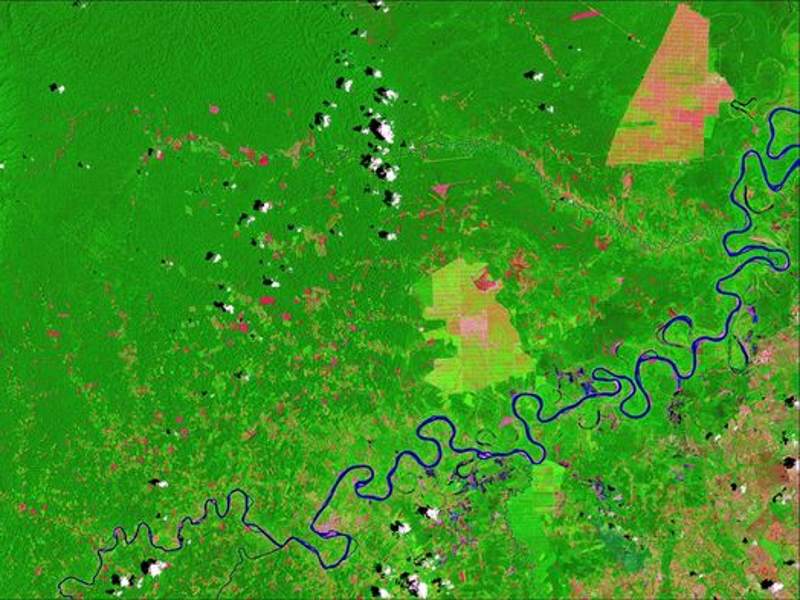

Antenor Vaz, formerly of the National Indian Foundation (FUNAI) in Brasília, the Brazilian government’s indigenous affairs agency, combed a wide range of records to map confirmed or reported locations of isolated groups in seven South American countries – Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru, and Venezuela. Then he laid that map over maps of oil and gas leases, mining claims, deforestation, and hydroelectric dams planned or under construction. Although most sightings of isolated people are inside parks or territories set aside to protect them, the maps show how these areas are increasingly hemmed in by large projects. Vaz, former assistant director of FUNAI’s office for people in isolation or initial contact, presented the maps at a conference of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America held here last month.

Vaz says his maps should serve as a warning. “This [rush of] development is the greatest risk factor for isolated indigenous peoples and those in recent contact,” he says. Isolated people, who live seminomadic, traditional lives in the forest, lack immunity to common diseases and are at risk when they make contact with outsiders.

Vaz notes that his maps do not include roads, which are a major threat because they tend to catalyze logging, deforestation, settlement, and further forest fragmentation. In southeastern Peru, for instance, unauthorized road construction has been creeping toward an area where a group of Mashco Piro people have repeatedly emerged from the forest.

In Brazil, ongoing political turmoil may heighten the vulnerability of indigenous groups. In January, the government shifted responsibility for drawing the boundaries of indigenous territories from FUNAI to the Ministry of Justice. Proponents said it would streamline the process, but critics, including FUNAI officials, say it will cut anthropologists and other experts out of the decision-making process. The Ministry of Justice is now reviewing demarcation proposals already in the pipeline.

Indigenous rights advocates in Brazil have won one battle. Brazil’s supreme court ruled yesterday in favor of two tribes that had challenged a measure that would have narrowed indigenous people’s territorial rights. Under the measure, tribes that could not show they occupied ancestral lands as of October 1988 – when Brazil’s current constitution came into force – would have lost claims to those lands. If the court had upheld the measure, it would have opened some currently protected areas to farming, ranching, and logging. The legal battle isn’t finished, however: The court put off a decision in a related case involving a third tribe.

Uncontrolled contacts

For the past two decades, Brazil’s official policy on isolated peoples has been to protect the territory they inhabit and allow them to decide when – or whether – to make contact. Other countries, including Peru, have based their policies on Brazil’s. But as the outside world closes in on indigenous groups, contact is more likely – and “no country is really prepared,” Vaz says. Contact is a process that can go on for decades, and experts say it is best handled by trained anthropologists, linguists, and health workers. It can take four generations for a group to build up resistance to common illnesses like flu, says Roberta Cerri Reis of Brazil’s Special Secretariat for Indigenous Health, who is based in Brasília.

But encounters often occur with few controls. Loggers, miners, and drug traffickers operate even in remote places. Aerial photos last year showed illegal gold miners within 20 kilometers of an isolated group of Yanomami people in the northern Brazilian state of Roraima, says Fabrício Amorim, coordinator of protection and localization of isolated Indians at FUNAI.

In Peru’s Madre de Dios region, members of the Mashco Piro group have made repeated and sometimes violent contact in recent years. Several times, missionaries and tourists were filmed stopping along a river and giving the people clothing and other items. After two people were killed by Mashco Piro arrows, in 2011 and in 2015, Peru’s Ministry of Culture set up a monitoring post and began to control access to the area, says Lorena Prieto, who heads the ministry’s office for isolated peoples here.

Rittma Urquia, the granddaughter of the man killed in 2011, says members of the Mashco Piro group told her they were angry that he allowed white people to watch them from his farm, located across a river from a beach they used. Urquia, who speaks their language and has served as a translator for the Ministry of Culture, adds that they complained that noise from small planes, possibly belonging to drug traffickers, had frightened game animals away. She believes officials should teach the group to plant bananas and cassava. But Prieto says that the Mashco Piro do not appear to be malnourished and have said they do not want to form a settlement.

“Foremost, we want to listen to them and respect their pace,” Prieto says. “We don’t know if they will form a [settled] community, but it will be a long time before anything like that happens.” Nevertheless, she adds, “We see [contact] as a long-term process that is probably irreversible.”