The Trump administration is not the only government that has been busy slashing funds for environmental protection. Brazil has been doing the same.

While Mr. Trump makes no bones about his desire to roll back environmental laws, Brazil’s president, Michel Temer, a signatory of the Paris climate agreement, has sent mixed signals. To his credit, Mr. Temer pledged in Paris to cut his country’s carbon dioxide emissions 37 percent below 2005 levels by 2025.

His actions since then tell a different story. Last year, the Environment Ministry’s budget was cut nearly in half, as part of a national austerity plan amid Brazil’s punishing recession. And the agency responsible for protecting Brazil’s vast system of indigenous reserves is being virtually dismantled by draconian staff cuts.

Funding for critical law enforcement to protect the rain forest from illegal timber cutting has also been decimated. In 2017, Brazil was the most dangerous country in the world for people defending the land or the environment, according to a tally by the group Global Witness, in collaboration with The Guardian newspaper. Forty-six people died. (The Pastoral Land Commission, a private advocacy group in Brazil for the rural poor, said at least 65 rural activists were murdered in disputes over development.)

If the government’s retrenchment on environmental protection continues, there may soon be nothing to stop the chain saws on the Amazonian frontier, where the rule of law can be weak and land is frequently seized and cleared illegally. This has implications beyond Brazil. The Amazon’s lush forests make up the largest reserve of carbon dioxide on the surface of the earth. This potent greenhouse gas is released when forests are burned or bulldozed and left to decay.

Brazilians are going to the polls on Oct. 7 to choose among nine candidates for the presidency, with a likely runoff later in the month between the top two vote-getters. The outcome will bear significantly on the future of the Amazon.

The current front-runner, Jair Bolsonaro, is a climate-change skeptic who has been called “the tropical Trump.” He has threatened to take Brazil out of the Paris climate accord. Another of the leading contenders, the former São Paulo mayor Fernando Haddad, is regarded as a moderate on the environment. Marina Silva, who as Brazil’s environment minister pushed to limit deforestation and encourage sustainable development in the Amazon, is running well behind in the latest polls.

Deforestation rates have been trending mostly upward since 2012 and will surely escalate if a raft of proposed laws and regulatory changes to weaken environmental protections are enacted. Brazil lost 2,682 square miles of Amazonian forests in 2017. That is almost nine times the size of New York City and 78 percent above the government’s own target for meetings its obligation under the Paris accord.

In an analysis published in July in the journal Nature Climate Change, 10 Brazilian scientists concluded that “the abandonment of deforestation control policies and the political support for predatory agricultural practices” will make it impossible for Brazil to to reduce carbon dioxide emissions to the level the country promised in Paris. Continued weak environmental governance, the scientists warned, could lead to the loss of up to 17,000 square miles of rain forest a year, endangering the entire Amazon ecosystem.

Why this change in policy? The scientists put it succinctly: “In exchange for political support, the Brazilian government is signaling landholders to increase deforestation.”

President Temer’s minister of justice is pushing plans to allow agribusiness to rent indigenous land that had been off limits to developers. Other proposals would effectively freeze the creation of new protected areas, open others to resource exploitation and block the mapping of boundaries of indigenous lands, potentially opening native communities and their forests to invasion by miners and ranchers.

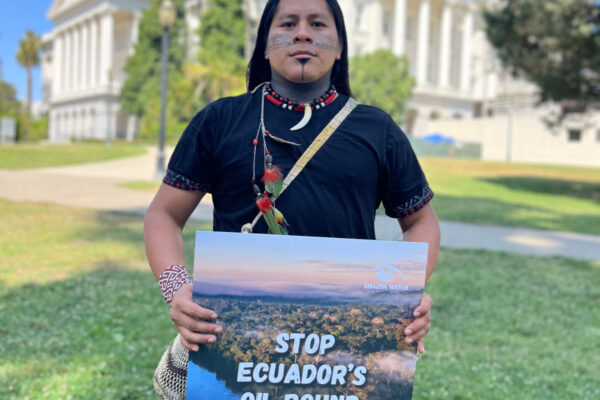

Indigenous territories contain more forest than all of the government’s conservation units combined, and historically Brazil’s native peoples have been far more effective in defending the rain forest than the government or private landowners.

The anti-environment agenda is being pushed by of a coalition of large landowners and agribusinesses in Congress (the “bancada ruralista” or so-called ruralists). Regular revelations of corruption involving government ministers, legislators – and also, President Temer himself – have provided them with cover to pursue regressive measures, like a proposed constitutional amendment that would prevent Brazil’s regulators from blocking environmentally unsound road and development projects.

Scores of such projects planned for inaccessible regions of the Amazon may be fast-tracked should the amendment pass and the environmental review process is gutted as a result, as now seems likely. For example, the 540-mile long BR-319 highway would, if completed, open a vast area in the central and northern Amazonia to deforestation.

Not only is little being done to prevent illegal land use, some laws have encouraged it. Last year, the “grileiro” or land-grabber, law legalized tracts of nearly 6,200 acres that were taken illegally – a boon to land speculators and others who seize public lands for their own use.

Not so long ago, Brazil was doing things right. Despite low global prices for soy and beef, the nation experienced a remarkable economic expansion while deforestation fell 60 percent from 2004 to 2007, demonstrating that environmental growth is consistent with economic growth. But now that demand for soy and beef on the global market is high, pressure on the forest is mounting. Deforestation is still well below historical highs. But that could soon change if the power of the agribusiness lobby is not checked.

The ruralists came into increased prominence toward the end of the administration of the Workers Party president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, and grew more powerful during the term of his successor, Dilma Rousseff. During Ms. Rousseff’s presidency, which ended when she was removed from office following impeachment, amnesty was granted to landowners who had illegally cleared forests, encouraging continued lawbreaking in the world’s largest rain forest.

Climate change has also increased the danger of catastrophic forest fires. In dry El Niño years, burned areas can greatly exceed what is cleared for cattle pasture.

The changing climate represents both a threat to the Amazon and a key reason for protecting its forests. Transpiration from tree leaves generates rivers of moisture in the atmosphere that act as conveyor belts bringing much-needed rain to Brazil’s heavily populated south and to Argentina. São Paulo, which already regularly runs dangerously short of water, will be a major victim if continued deforestation removes this water vapor transport that fills the reservoirs on which the city, South America’s largest, depends.

The Amazon forest itself would also suffer. As more of it is cut, the huge volume of self-generated rainfall it needs to remain verdant is steadily reduced, worsening droughts made more frequent and severe by global warming. At some point – we are not sure how close we are to this critical tipping point – the entire ecosystem dries out.

Brazilians have consistently said in opinion polls that they want to preserve the Amazon. But in the current atmosphere of unbridled greed and corruption in high places, the voices for wise policy are often drowned out.

Brazil alone has not created the deforestation problem, and neither can it address it alone. Demand for Brazil’s beef from Western nations, and increasingly from China, has created an enormous temptation to cut the forest to turn a quick profit.

Importing nations and Brazilian soy traders and beef producers must live up to their pledges that they will not buy products produced on cleared forest. And global financial institutions must stop funding projects that result in deforestation. They should also increase their assistance to Brazil and other tropical countries to help them maintain their forests and pursue nondestructive alternatives to cutting them.

Only then, can we insure that the Amazonia forests, the living heart of Brazil – and of the world – will remain intact.