On the banks of Brazil’s lower Xingu River, a toxic controversy looms large, threatening to heap insult upon the grievous injuries of the nearby

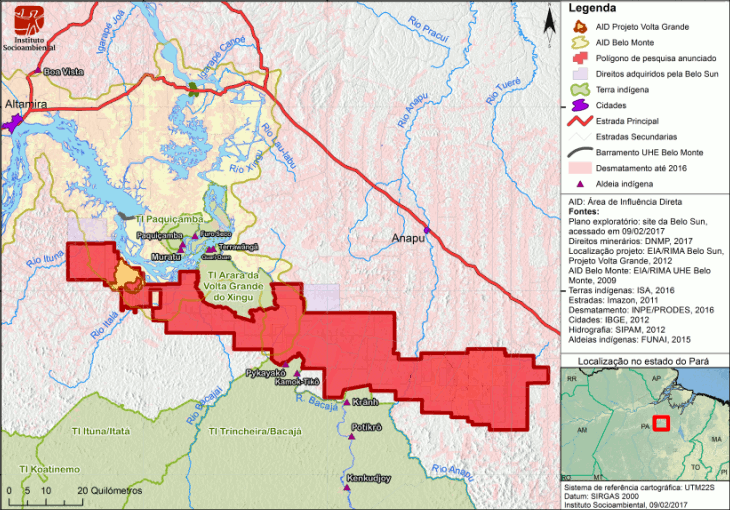

Belo Monte hydroelectric dam. In early February, the Canadian company Belo Sun received the final operational licence for its proposed Volta Grande mine from the Pará state environmental agency (SEMA-PA). The sprawling nearly 620 square-mile concession would become Brazil’s

largest open-pit gold mine, straddling the territories of three indigenous peoples and other traditional communities that are already reeling from the many social and environmental impacts of Belo Monte.

Since field research for the mine began in 2008, the peoples of Xingu have publicly decried the occurrence of human and environmental rights violations in the lead-up to the mine’s construction. They have also warned of the likely negative social and environmental impacts that the mine project will cause, and recently they and their allies have taken these complaints to the courts.

First, they have denounced that some of the land on which the mine will be constructed was purchased illegally, given that it is land that the federal government

designated for agrarian reform in the 1980s. Second, the mine is close to the village of Ressaca, a community of 300 families, all of whom would be displaced and have not been relocated by the company as required.

Third, local communities

fear that the project may well end in a tragedy, like the

Samarco Mariana dam collapse in 2015, given that Belo Sun intends to use a mining waste storage dam similar to the one used in Samarco. And even if the mine did not suffer a major catastrophe, the environmental and health impacts of the liberal application of

cyanide, arsenic, and other toxic chemicals frequently employed in gold mining would lead to dire implications for communities already dealing with the

dramatic changes to their way of life caused by the Belo Monte dam.

In a small piece of good news for communities, on February 21st a judge

issued a 180-day injunction on the license in response to a legal complaint filed by the local public prosecutor’s office. In doing so, Judge Álvaro José da Silva Souza recognized that the license issued by SEMA-PA had ignored the community’s complaints, that the allegations of illegal land purchases warrant further investigation, and that the company had not fulfilled its promises to properly relocate the families that would be displaced by the mine. As Judge da Silva said in issuing the injunction, “I understand it to be completely absurd and unjustifiable that the families are currently still at the mercy of their own luck.”

The ruling gave the company 180 days to develop a plan to reallocate impacted communities. The company insists that it will

appeal the decision.

Public hearing airs concerns and condemnations

Such concerns were front and center at a March 21st

public hearing in the city of Altamira, where Belo Monte’s affected communities aired their grievances to a panel of government and corporate representatives, including from Belo Sun.

After attending the hearing, local analysts described the companies’ neglect of the affected communities as an intentional tactic meant to give them no recourse but to accept meager resettlement plans far from the river and their traditional livelihoods.

During the hearing, Janete Carvalho, an environmental licensing agent from the Brazilian indigenous agency (FUNAI), recalled the toxic legacy of the 2015 Samarco disaster on the Doce River, which killed nineteen people and left another 700 homeless, as a warning to those threatened by Belo Sun. “The closest indigenous territory to Samarco is more than 300 kilometers away and the Krenak people still do not have enough clean water to live,” she stated. “Any accident by Belo Sun will create a situation of ethnocide. The risk is unacceptable.”

FUNAI representatives reiterated that their office does not recognize the mine’s original environmental impact studies and demanded that a new, more rigorous, analysis be conducted that respects the communities’ right to

Free, Prior and Informed Consent.

“We would like prior consultation to be conducted,” said Chief Gillarde Juruna of Miratu village, located only six miles from the mine’s epicenter. “I was born and raised in that region. We never asked for any project and now there are two of Brazil’s largest projects there. We have no guarantees.”

To address these irregularities, FUNAI filed a

lawsuit against Belo Sun in February charging that its installation license was issued by

completely ignoring the indigenous agency and its demands that the project’s impact assessment and licensing adhere to a specific study of its

impacts on nearby indigenous communities. That case is currently pending.

“Who are you lying to, Belo Sun?”

At the close of the contentious hearing, public prosecutor Humberto Alcântara Ferreira Lima raised serious concerns about the true size and scope of the Volta Grande mine. He revealed a major discrepancy between the mine’s projected gold production as reflected in the license granted by SEMA-PA (pending resolution of Judge da Silva’s injunction) and what the company is telling its investors it will extract. Licensed on the basis of a 2012 estimate that the project will yield roughly 37.7 million tons of gold, Belo Sun has separately touted different projection numbers to its investors: 88.1 million tons in 2013 and most recently 116 tons in February of this year.

“What is the real dimension of Belo Sun’s Volta Grande gold mining project?” asked Mr. Lima. “The one disclosed to Brazilian public institutions or the one disclosed the company’s shareholders, which is more than three times as large? Who are you lying to: the investors or the [licensing agencies]?”

Like Belo Monte, Belo Sun is likely to cause more harm than good

One thing is clear: Belo Sun’s mega-mine is shrouded in irregularities and incalculable risk, much like its neighbor, the Belo Monte dam. Like Belo Sun, local communities and allies warned of the serious environmental and social impacts of Belo Monte, and, unfortunately, those

dire warnings have proved prescient. And also like Belo Monte, the corporate interests behind the mine demonstrate neither concern nor prudence, rushing instead to initiate operations at any cost.

Belo Sun is owned by Canada’s Forbes & Manhattan, a private merchant bank. Canadian mining giant Agnico Eagle Mines is the company’s largest shareholder, with a

19% ownership of Belo Sun. Known for its notorious

Malartic urban gold mine in Quebec, Agnico is subject to no fewer than 4,000 violations of environmental laws and regulations and is subject to a CAD $70 million lawsuit for its impacts on local residents.

The struggle to preserve what is left of the lower Xingu’s environment and communities from another catastrophic mega-project is not over. Even as political and economic forces line up behind Belo Sun and the region’s untapped riches, the local communities and their allies prepare to resist them. Amazon Watch has been standing with the communities of the Xingu for many years, and we will we not give up our support for them now!