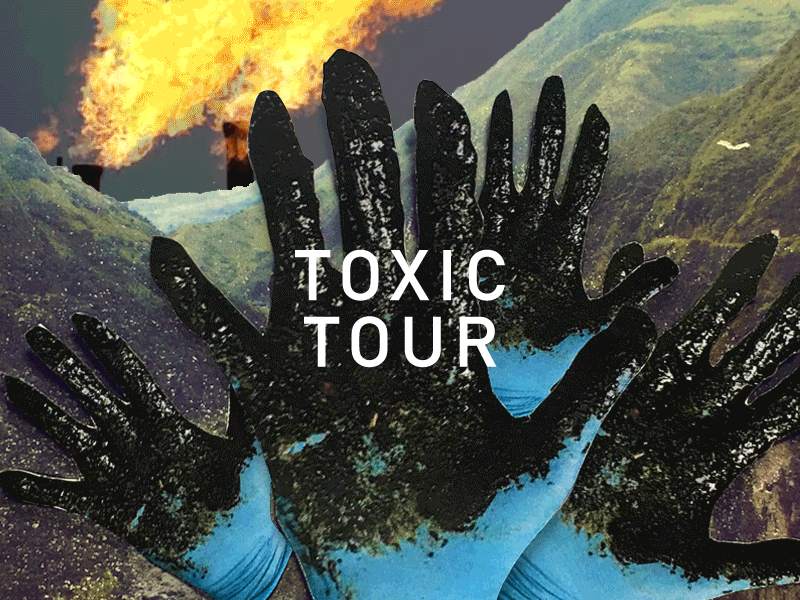

We’re excited to share an amazing virtual reality piece by RYOT/Huffington Post that gets you on the ground to the front lines of two key oil battles in Ecuador’s Amazon. Accompany Nina Gualinga, an indigenous youth from the Kichwa community of Sarayaku as she tours former oil fields of Chevron and gets an up close look at one of the worst oil disasters on the planet. We also meet Manari Ushigua and the Sápara, an indigenous group of 500 in Ecuador’s southern, pristine rainforests that are working to defend their lands, lives, and culture from new drilling plans by the Ecuadorian government and Andes Petroleum.

Nina Gualinga is an environmental and indigenous human rights warrior. She was born and raised in Sarayaku, an indigenous community from the Ecuadorian Amazon. Here is her story.

My life changed when I was seven years old. That’s when an oil company came to my village.

I remember the first time I saw the company representative. I didn’t like him. He saw us, but he didn’t really see us, like he had an agenda that didn’t include us. He was bald and pale, sick-looking.

My village gathered in a big meeting. The women of the village were angry and told him in Runa Shimi, our mother tongue, to go back to where this man came from. We would never sell our lands to the oil companies. That is when I began to understand who he was. He offered us $10,000. At that time we were nearly 1,000 people in our village. That’s $10 per person and our territory is approximately 136,000 hectares of pristine rainforest. Even at seven years old I knew it was a bad deal and an insult to my people. When he realized that a couple of dollars wouldn’t fool us, he talked about education and health care. Though I didn’t understand Spanish, I knew that everything he was saying was a lie. I didn’t know what oil exploitation was, but I imagined my home destroyed: sick people; flames everywhere; dead animals and trees; my village in ashes. I felt an angry heat rise in my body, the kind only a little girl who is about to have her future taken away can feel.

I grew up very close to my grandmother, surrounded by many animals, bathing in the Sarayaku River, drinking water directly from the springs — and I still do. I was a very happy child. How could I not be? I was blessed to be born in this place and I knew it.

In March 2016, I travelled from a small town in the southern part of the Ecuadorian Amazon called Puyo, the capital city of Pastaza province. Traveling through this rainforest region makes you weary and slightly exhausted. It requires a lot of patience and determination, as travel options are limited. You can get around by canoe, bus or on rare occasions — depending on the weather — using small airplanes that require a landing strip. Leaving Puyo, I journeyed nine hours by bus to eventually reach Lago Agrio, an old oil boomtown, whose name translates to “Sour Lake” in Spanish. Lago, as the locals call it, is known for its high crime rate and prostitution.

We stopped by a defunct operation camp of another oil company that had also entered our region. The camp could not produce enough oil and was not worth the upkeep. As we stood with our faces pressed against the net looking in, I thought about how this should have been forest, home to indigenous people, without fences and machines pumping out crude oil.

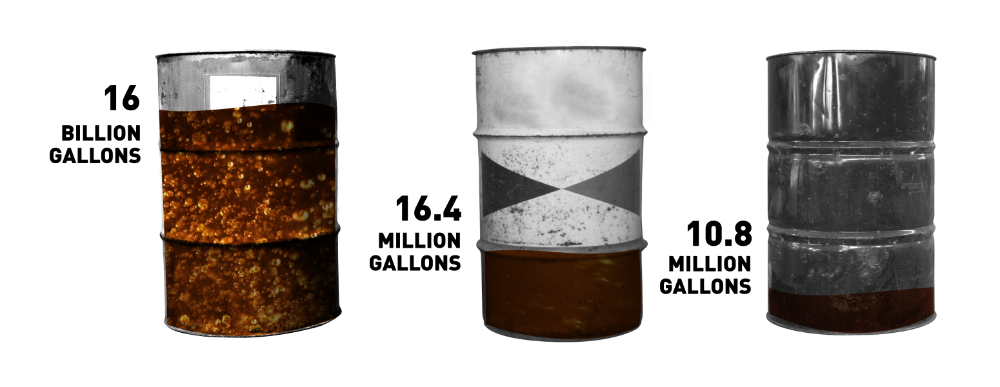

18 billion gallons of toxic wastewater dumped into streams and rivers by Chevron. 16.8 million gallons crude oil spilled in Ecuadorian Amazon. 10.8 million gallons Exxon-Valdeez oil spill, often considered the worst in history.

We continued our journey for a couple more miles. At the edge of what looked like regrown forest there was a little trail of black crude waste. You could smell it. The oil company had constructed thousands of unlined open-air pits on the jungle floor within the span of 20 odd years, some of which they covered up with dirt. The contaminant had leaked into surrounding soil and groundwater, springs and rivers: it poisoned the land of our people and animals.

What was this place like before the oil companies and new settlers came? It must have been like back home: majestic forests with tall trees, mysterious caves, crystal clear rivers and myriad wildlife species. I imagined hearing birdsong and whispers of the winds, and seeing the sky full of stars at night. I imagined children playing in the sand by the rivers — always wary of the anaconda — and fresh water fishing from canoes. You could probably hear the sound of wood beating against wood when the mothers smashed the yucca or chonta to make the delicious fermented drink, chicha. The men would walk through small paths, almost invisible, through the forest, camouflaged with images painted all over their bodies, bringing home food to their families.

To watch this 360° video, you’ll need the latest version of Chrome, Firefox, or Edge/Internet Explorer.

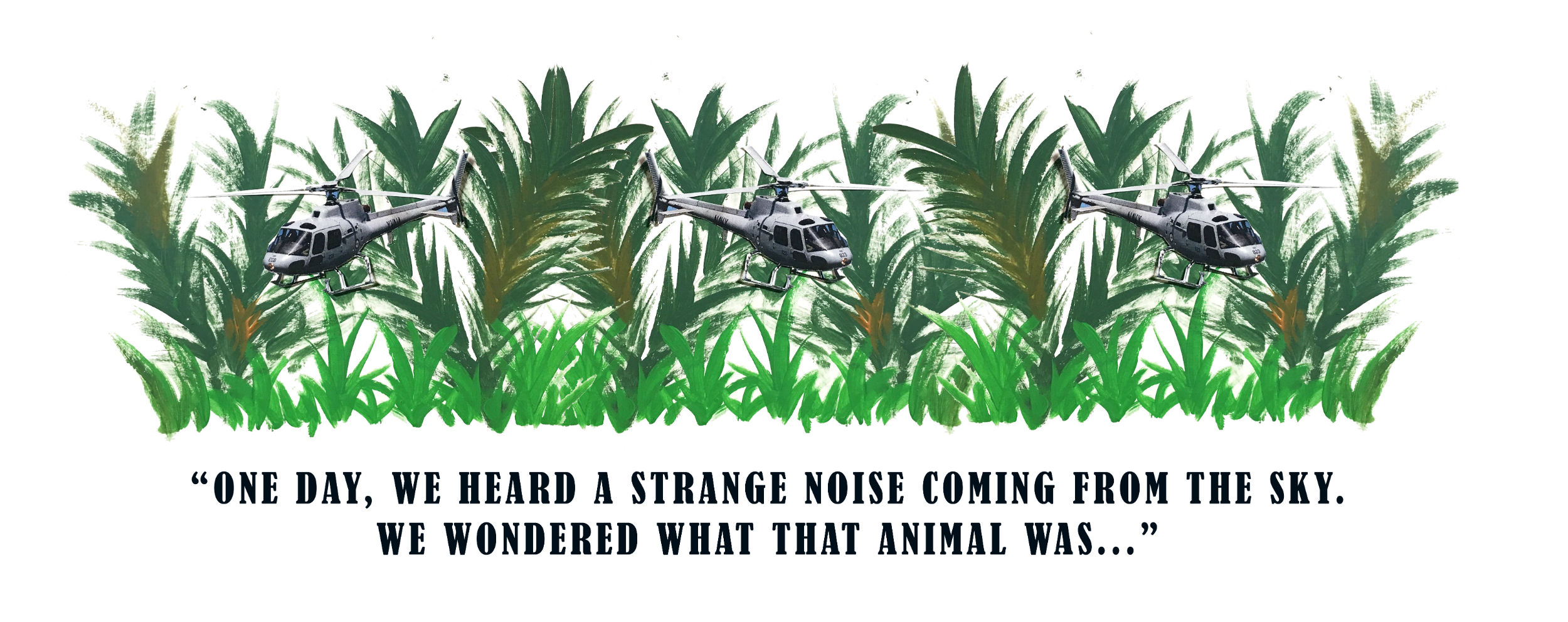

One man from the Cofán indigenous tribe still remembers how it begun. He was an only child. “One day,” he recalls, “we heard a noise coming from the sky, people panicked and ran into the woods to hide. Strange things came from the sky and we wondered what animal it was. When the helicopters left, the men went to where they had landed. One of the men was my father. They came back with three things: something sweet, something that smelled nasty and something that was flammable. The sweet thing was sugar, so we kept it. The nasty smelling thing was cheese, we threw that away. The flammable liquid was diesel, which was useful for lighting fires. Soon the trees were cut down, more and more foreign people came and the people of the village never really knew what was going on. Roads were built, machines were installed and soon black liquid was being pumped up from the soil. The people working with the machines told the indigenous people that the black liquid was good for them, it was good for the body, for the skin, and even made them rub it onto their bodies. We wanted to stop them, but we could do nothing because we couldn’t speak Spanish. And once we learned Spanish there was nowhere we could complain.”

Shaman, Leader, and Indigenous and Natural Rights warrior Manari Ushigua (center) with Sapara tribesman Francisco and Felipe Ushigua. Photo credit: Ben Roffee.

My heart sank as he told me this. I understood perfectly well what had happened, the same thing that would have happened in my own home village had we not been able to stop it. The oil companies came to these pristine forests, backed by our own government. They took what they wanted and wiped out cultures, completely disregarded the indigenous people, killed animals and ruined sacred places. In the end, the people couldn’t do anything about it because they couldn’t speak the language of the people destroying their lives! The same destruction is still going on to this day.

To the south of Lago live seven different ethnic groups: Achuar, Shuar, Shiwiar, Sapara, Kichwa, Andoas and Waorani. Two of the world’s last indigenous tribes in voluntary isolation, the Taromenane and Tagaeri, also live in the region, in the Yasuni National Park, one of the most biodiverse places on earth. Though it’s a protected area, recognized as a world heritage site by UNESCO, the Ecuadorian government recently gave drilling concessions to oil companies. Living in isolation means that these groups are even more dependent on their surroundings than other indigenous groups. They’ll face extinction if the rivers become polluted or the animals disappear. In Waorani territory, the dark shadow of oil has led to disputes and even killings between tribes because of land reduction and resource scarcity. For such sensitive people, the smell, the noises and the reduction of territory and food sources causes enormous harm because it changes their way of life drastically. As it becomes harder to survive, the only weapon they have to defend themselves is their spears, as it has always been.

Southwest from the Yasuní is my home village Sarayaku. Most indigenous communities of the southern Ecuadorian Amazon — which is still pristine, roadless, rainforest — are aware of the damage oil companies have caused our brothers and sisters in the north and we have decided to fight them in our territories. A network of indigenous warrior women has grown over the past few years. We are protesting, marching and demanding the oil be kept in the ground. We are daughters, we are sisters, we are mothers, we are grandmothers and aunts. They left us no choice but to fight back. And we are not stopping until we know that we can leave a better world for future generations.

I will not give up and I will not stop until we have peace. This is my promise to the soil, to the rivers, to the mountains, to the wind, to the trees, to my people, to my unborn children and to yours. It’s a promise I made to myself a long time ago as a little girl.

Nina Gualinga

Daughter of the First Uprising