This report was originally published on December 11, 2014 by Agência Pública, with the support of Mongabay, in two parts: “The Battle for the Munduruku Borders” and “Decades of Struggle for the Tapajós”, both written by reporter Bruno Fonseca. They were adapted and will be published on Global Voices in three installments.

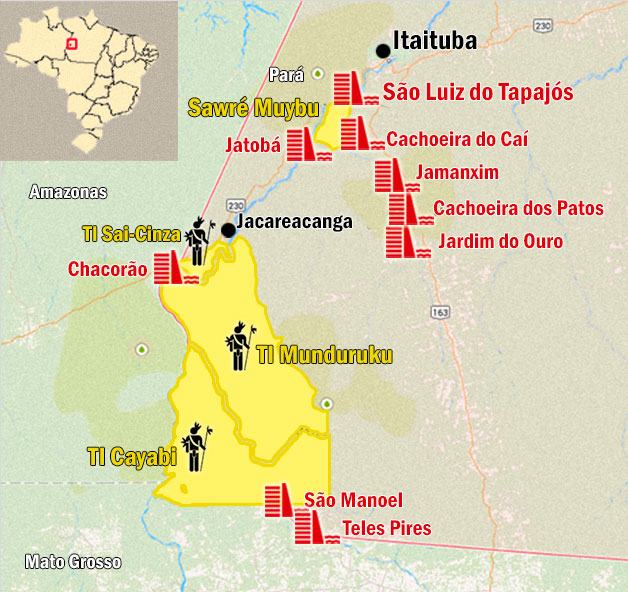

The Munduruku people are made up of more than 13,000 men, women and children, who live by the 850 kilometers of the Tapajós River and its tributaries located in north and center-west Brazil. Most of their villages will feel the impact of a government project in the region: the construction of seven hydroelectric dams on the Tapajós and another two already underway on the Teles Pires river, a branch of the Tapajós that runs between the states of Mato Grosso and Pará.

The Munduruku have four areas of indigenous lands officially sanctioned in both states. But the territory of Sawré Muybu, considered sacred, was never officially recognized by the Brazilian government. Its borders could become a major obstacle in the path of President Dilma Rousseff’s project to explore the Tapajós watershed.

The official demarcation of this territory could deter the construction of one strategic hydroelectric plant: the São Luiz do Tapajós dam, which, if raised, will be the third largest in Brazil, with a budget estimated at R$ 30 billion (about US$ 11 billion) and an installed capacity of 8.040 megawatts. The dam will flood significant parts of Sawré Muybu, rendering life impossible in the area. Among the anticipated changes, there is the shortage of fish and game – essential items for the village’s survival.

To solve this deadlock, recent studies commissioned by the government suggest that the Munduruku be removed from the area. In response, the public agency National Fundation for Indiengous People (FUNAI) pointed out that this idea is unconstitutional and recommended the suspension of the plant’s license, according to a September 25 internal report to which Pública gained access.

The removal of indigenous peoples is prohibited by Article 231 of the Brazilian Constitution. In the project’s defense, the government argues that since Sawré Muybu was never officially demarcated it cannot be recognized as Munduruku land – provoking the wrath of warriors and village chiefs all across the Tapajós basin.

The federal government had previously scheduled an auction for the rights to dam the São Luiz do Tapajósto for December 15, 2014, but authorities was forced to postpone it until an undisclosed date in 2015 because the environmental permit hasn’t been issued. The reason behind the delay was FUNAI’s Indigenous Component Study, a report that indicates the impact that the plant will have on inhabitants, wasn’t concluded.

The misguided licensing process revealed that the government is not too attentive to the indigenous matter. The Munduruku are the most vulnerable in terms of the environmental transformations that the dam will trigger.

Pressured by actions from the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office (MPF), the government established a consultation schedule with the traditional populations. Prior consultations are a requirement for many of the MPF’s actions in the state of Pará. They are based on the indigenous peoples rights guaranteed by the Brazilian Constitution and by Convention No. 169 from the International Labor Organization, to which Brazil is signatory.

The convention establishes that governments are obligated to “consult the interested peoples” before taking any action that might interfere with their territory and way of life, as well as to provide them with “the opportunity to participate freely at all levels in the formulation, implementation and evaluation of measures and programmes that affect them directly”.

After announcing the consultations, however, the head of the Presidential General Secretariat, Gilberto Carvalho, declared they will not be deliberative, meaning nothing that the Munduruku say could deter the dam construction. “The consultation should be made to meet their demands, to lessen the impacts, but it won’t be impeditive”, he said in a interview to BBC. “We won’t waive the construction of the dam.”

The Munduruku takes Sawré Muybu demarcation into their own hands

The Munduruku, whose warring history precedes their first registered contact with the Portuguese in 1768, began employing a new strategy in October to fight for their cause. With scythes and machetes, they began to open a trail four meters wide and seven kilometers in length. It is the self-demarcation of the indigenous land of Sawré Muybu.

The Munduruku of Sawré Muybu have announced the self-demarcation after seven years of waiting for action from FUNAI, who is responsible for the official demarcation of indigenous lands. It took the agency that long to create a document recognizing the land as historically occupied by the Munduruku and also establishing its boundaries (“Detailed Written Report of Identification and Delimitation of the Indigenous Land of Sawré Muybu”). The document was concluded in September 2013, but its official publication has been held up by FUNAI’s presidency.

Pública gained exclusive access to the report and published it in its entirety. At 193 pages, it includes a thorough assessment of the historic bonds the Munduruku have with this piece of land. The report indicates that the 113 people who live there will have their “physical and cultural reproduction” threatened by the hydroelectric dams, and it concludes that “the state’s acknowledgement of Sawré Muybu is indispensable to confer legal security to the indigenous peoples and to guarantee that their rights are respected.”

To open the trail, the Munduruku have united with the riverbank people, who will also be affected by the dams. The group also counts the help of social scientist Mauricio Torres and historian Felipe Garcia, volunteers who operate the GPS equipment. They follow the exact coordinates of FUNAI’s demarcation map, currently awaiting a green light for publication in the country’s capital, Brasília.

Excluding its unofficial character, there is little difference between the work of this team and that of an official demarcation. Minimum security is among them, however. Without the government’s endorsement, the demarcation team faces many risks.

A week prior, the Munduruku were surrounded by a group of loggers with motorcycles and trucks. Days later, they approached a group of 300 independent miners who were extracting diamonds inside the land. Upon being warned about the self-demarcation, the miners replied they would only leave if the demarcation were official.

The entry gate to the world

Worried about the impact on their territory as a whole, the Munduruku people from all over the basin have united in the belief that Sawré Muybu is a fundamental part of their culture that needs to be defended. Along with its residents, the land is home to the sacred soil Daje Kapap’ Eipi, where the Munduruku believe that the Tapajós river, the animals and the first people were born. Given its spiritual importance and the nature of the political conflict in which it is currently immersed, the place could be considered a kind of “Munduruku Jerusalem”.

“This is the entryway to our territory, we came to protect this land for our children and grandchildren. For the future”, says Saw Rexatpu, a Munduruku warrior and historian, after a long day of work with the self-demarcation team. “Our great-grandparents died fighting here and we’re going down the same path. If I die here, I will leave my story.” He travelled for three days to answer the call of Juarez Saw Munduruku, the village chief at Sawré Muybu.

But what if the strategy goes awry and the government tells them to leave? “We won’t leave”, says the chief, his calm face unchanged. And what if the police eject you by force? “It will be the end of our world because we’ll only leave here dead.”