There are approximately 1.5 billion cows in the world, a population second only to humans among large mammals. They can be raised anywhere: from the Arctic to the equator, on prairies, in deserts and on mountains.

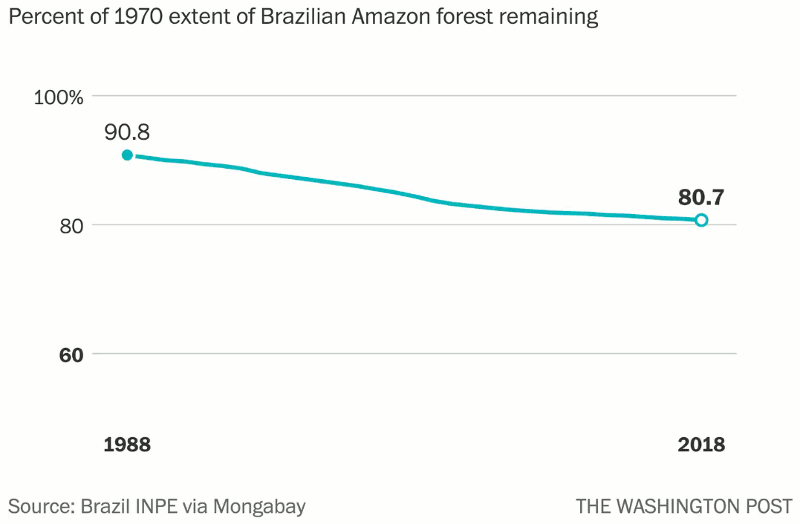

Cattle ranchers in the Brazilian Amazon – the storied rainforest that produces oxygen for the world and modulates climate – are aggressively expanding their herds and willing to clear-cut the forest and burn what’s left to make way for pastures. As a result, they’ve become the single biggest driver of the Amazon’s deforestation, causing about 80 percent of it, according to the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies.

The ecological devastation is done in the service of the surging demand for beef. About 80 percent of Brazil’s beef is consumed domestically, said Nathalie Walker, the director of the tropical forest and agriculture program at the National Wildlife Federation.

But the real shift can be traced to the global market, particularly in Asia, where demand is growing at a much faster rate than it is domestically. “The expansion is driving the deforestation,” Walker said.

From 2010 to 2017, beef exports climbed 25 percent, to 1.5 million tons, according to the Brazilian Beef Exporters Association. To accommodate that growth, cattle ranchers have been pushing their herds into the Amazon, clear-cutting and burning the forest as they go. Today nearly 40 percent of Brazil’s cattle population is located in the Amazon region, according to government data.

Hong Kong is the biggest global importer of Brazilian beef products, bringing in about $1.5 billion worth in 2017, according to the Brazilian Beef Exporters Association. China is second, at nearly $1 billion, followed by Iran, Egypt and Russia. The United States, which imported $295 million in beef, came in sixth.

The underlying toll of the industry’s growth has spurred talk of a boycott. The finance ministry of Finland, the current chair of the European Union, called on the bloc and Finland to “urgently review the possibility of banning Brazilian beef imports,” in a statement last week, Reuters reported.

Alternatives to boycott

Walker says there are other options for combating deforestation. In 2009, for instance, as a result of an effort by the environmental group Greenpeace, Brazil’s three largest meatpackers agreed to a moratorium on beef purchases from Amazon ranchers involved in deforestation. That year, the government spearheaded a separate but similar agreement with beef retailers and exporters.

Subsequent research has shown that those agreements helped reduce deforestation. But they are narrow in scope and spotty in their implementation: Walker said they deal only with about 10 to 20 percent of all cattle-driven deforestation. One major blind spot, she said, is that they don’t deal at all with the ranches where cattle are born and spend the first several months of their lives.

Another path would be to increase the productivity of existing Brazilian cattle ranches. “There are huge areas of already cleared land,” Walker said. But clear-cut forest doesn’t make for quality cattle pasture, and as a result the country is averaging just one cow per hectare (2.47 acres) of pasture. Walker said better land management could let ranchers “triple their production without cutting a tree.” But initial costs and know-how are proving to be hurdles.

The election of Jair Bolsonaro, a far-right former army captain who pressed a pro-business agenda to the country’s natural resources, as president created another obstacle. Since he took office in January, environmental enforcement actions have dropped, deforestation has increased and the head of the federal agency tracking deforestation was fired after criticizing the president’s policies.

The role of outside finance

Many experts on the Amazon have concluded that as long as Bolsonaro remains in power, efforts to stop deforestation will have to come from outside the country. Moira Birss, the campaign director of the finance program at Amazon Watch, an environmental group, recently wrote a report examining the role of U.S. and European finance companies in supporting Brazilian agribusiness.

Major investment companies such as the Capital Group, BlackRock and Vanguard collectively hold hundreds of millions of dollars in investments in Brazil’s major meatpackers, Birss’s report found. “Foreign investors have enormous influence over what happens in the Brazilian Amazon,” according to the report. “Big banks and large investment companies play a critical role, providing billions of dollars in lending, underwriting and equity investment to soy and cattle companies. This capital and financial security enables agribusiness to maintain and expand operations, causing further devastation to the Amazon.”

JBS, for instance, is Brazil’s biggest meatpacker, controlling about 35 percent of its beef export market, according to data compiled by Trase, an organization that tracks global supply chains. Despite being party to Brazil’s major deforestation agreements, the company has been caught numerous times in recent years sourcing its beef from ranchers engaging in illegal deforestation. The company’s leadership has been implicated in numerous bribery and corruption scandals involving government officials. The company did not respond to a request for comment.

Those scandals haven’t deterred American investors, who own well more than $1 billion in JBS stock, according to Amazon Watch. The company’s stock price has roughly tripled since Bolsonaro’s election, hitting a record.

That rise has “everything to do with the fact that JBS suppliers are being provided increased access to ranching land – deforested land, that is – under increasingly lax environmental enforcement under Bolsonaro,” Birss said.

Birss’s organization has singled out financial services firm BlackRock, which holds more than $200 million in JBS stock on behalf of its investors, as an example of American interests financing Amazon deforestation. After Bolsonaro was elected, the company put out a bulletin highlighting his “reform agenda,” including “spending curbs, privatizations and a loosening of labor market laws.” This year BlackRock hired a country chief for Brazil for the first time in seven years, citing the need to “accelerate growth and drive innovation for clients” with investments there.

In an interview, a BlackRock representative said that like the majority of the company’s investments, its holdings in JBS are primarily through various index and exchange-traded funds selected by the individual investors that make up its customer base. “Our obligation as an asset manager and a fiduciary is to manage our clients’ assets consistent with their investment priorities,” said Farrell Denby, vice president for corporate communications. He added that BlackRock reviews companies for “sound corporate governance practices, including how companies manage the material environmental and social factors inherent to their business models.”

Amazon Watch and other environmental groups are pressuring financial firms to do more. They point to Legal & General Investment Management (LGIM), a large United Kingdom investment firm, which this year announced it would be cutting a number of polluting companies from its portfolio of “ethical” investments, and using its remaining shares in those companies to vote against board members who “fail to demonstrate sufficient action” on climate issues.

At a “pivotal point”

Walker, with the National Wildlife Federation, agrees that “it would be helpful if those big finance companies had deforestation policies that they implemented.” She added that consumers can play a role, too, by pressuring companies they buy from to adopt similar policies and not source materials from farms and ranches that cut down and burn the rainforest.

“Those buying Brazilian beef should say we want deforestation-free beef,” she said. But she acknowledged that finding out exactly where a given product comes from can be difficult. Walker said people interested in the issue should explore the trade data maintained by Trase, which shows the flow of Brazilian beef from exporters to U.S.-based importers.

“We’re clearly at a really pivotal point for the Amazon,” she said. “If you care, show you care. If you’re a supply chain actor, show your suppliers. The solutions are out there.”