Reposted with permission from Fusion.

Cuninico, Peru – No one ever expected Cuninico, a small riverside fishing village tucked in the heart of the world’s largest rainforest, to run out of drinking water. But it happened last June.

Since then this remote Amazon hamlet has relied on state-run oil company PetroPeru to deliver shipments of bottled water from the nearest city, nine hours down river.

Cuninico’s problem isn’t a lack of water, rather a surplus of oil. After a state-owned pipeline burst last June, some 2,000 barrels of oil leached into a nearby tributary, poisoning the Marañon River, which for generations has been the main life-support system for the 150 people of this village.

Community members say doctors have instructed them to avoid drinking the river water or using it to cook. Fish have become toxic, crippling the local economy and jeopardizing food security.

“We’re very worried,” community leader Galo Vasquez told Fusion during a recent visit to the village. “Petro Peru has said they’re almost done cleaning up the spill and that they will not supply us with water anymore. But the water here is still contaminated. You see white foam on top of it, as it comes down the stream and enters the river.”

Cuninico is a victim of Peru’s aging oil pipeline, the Oleoducto NorPeruano, built in the 1970s to take crude from the northwestern Amazon basin to a refinery on the Pacific coast.

But oil drilling is still booming in this region, which provides about one-third of Peru’s daily output.

Over the past 15 years, dozens of villages located near oil wells in the Northwest of Peru have had to deal with similar oil spills that have poisoned rivers with dangerous levels of cadmium, lead and other toxic materials.

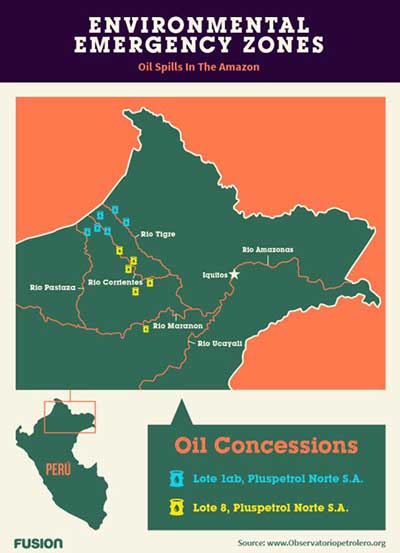

Pollution along the Marañon, Tigre, Corrientes and Pastaza rivers has reached such levels of toxicity that Peru’s Environment Ministry has declared all of them environmental emergency zones over the past two years.

“Many of our brothers have already died from poisoning,” Carlos Sandi, a leader of the Achuar tribe said during a recent visit to the capital city to meet with government officials. “In the 21st century, we cannot allow the Peruvian state to condemn indigenous people to death.”

Indigenous communities from affected areas have repeatedly lobbied the government and oil companies for reparations, environmental cleanup and public-health initiatives. But three years of talks have produced little more than a diagnosis of the problem.

Still, some see new reason for hope.

The lease on one of Peru’s most productive oil lots, known formally las “Lot 1AB”, expires in August. Indigenous leaders hope that will provide an opportunity to negotiate with the government, which is eager to continue drilling in the jungle to meet the demands of a growing economy, but without generating any more civil unrest.

“The government is trying to reach a deal with us because they don’t want oil production to stop; they don’t want to stop receiving money,” Alfonso Lopez, president for the Federation of Kukama Communities, told Fusion.

“They want to negotiate so that we enter consultations over the [next concession] of the oil lot,” Lopez said.

Part of that negotiation will mean coming to terms with environmental damages caused thus far. Four tribal federations are seeking reparations for the pollution generated by 40 years of oil drilling in Lot 1AB, first by Occidental Petroleum, and now by Argentine company Pluspetrol.

The indigenous associations, with the help of technical experts, are negotiating as a bloc to demand water-treatment plants, the identification of polluted sites, and land titling.

But in some parts of the jungle, indigenous community members are already pushing for more drastic measures, as seen in this video filmed by local activists last month.

In January a group of 400 Achuar villagers armed with spears occupied 14 oil rigs in Lot 1AB to demand some $10 million in reparations from Pluspetrol before the company’s contract expires in August. Another 200 members of the Kichua tribe blockaded the entrance to the Tigre River to prevent Pluspetrol’s barges from shipping oil out of the area.

The company said in a statement that the communities that were protesting at the oil lots came from outside areas. The company added, however, that it was willing to negotiate the issues “in a climate of social peace.”

Achuar leaders rebuffed Pluspetrol’s statement.

“Our brothers don’t believe in documents anymore; they want concrete measures and results they can touch,” Achuar leader Carlos Sandi said on Feb 5, more than a week into the ongoing occupation of the oil rigs, which continues today.

“We want negotiations…but if the government and oil companies do not respect our rights, more of this could happen,” warned Lopez, the Cucama leader.

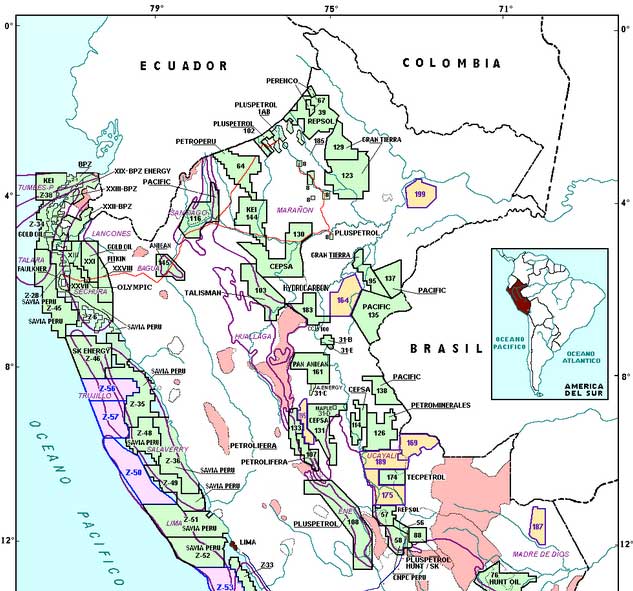

Curiously, these conflicts have not dampened the thirst for oil drilling in the Amazon. In fact, Peru is already pushing for up to 20 new oil and gas concessions in its Amazonian territories.

In December, while Fusion visited two oil spills caused by pipeline leaks around the Marañon River, Peru announced it will lease seven more oil lots in the rainforest, which cover an area about the size of Massachusetts. The new oil lots are highlighted in yellow.

Government officials justified the move by arguing that Peru needs to boost its oil production to meet increasing energy demands. The country’s current daily output, according to hydrocarbons regulatory agency Peru Petro, is around 70,000 barrels, enough to meet about one-third the demand of the country’s growing economy.

“Every nation has the right to seek energy independence,” Luis Ortigas, the president for Peru Petro told Fusion in an interview in his Lima office.

“Our country is underexploited,” he said, adding that Peru has only completed exploration in four of its 18 oil basins.

Ortigas said he isn’t concerned that the environmental mess left in LOT 1AB will be repeated.

“The pollution found there stems back 30 years ago, when oil production was really a contaminating activity,” he said. “Technology has improved so much that indigenous people can perfectly coexist with oil activities nowadays.”

But even with new technologies, Peru continues to do some things the old way, especially when it comes to carving wide roads into the jungle that run parallel to oil pipelines.

Bill Powers, an engineer and environmental consultant for U.S. NGO e-tech international, says such roads were once needed for engineers to access pipelines, but now monitoring can be done remotely and access facilitated via helicopter or smaller trails. Still, Peru Petro, in its eagerness to court new investment, recently approved a request to build a 200-km road through the jungle to service an oil pipeline operated by Anglo-French company Perenco.

“Once you build a road, there is no turning back the clock,” Powers said. “Roads open up the region to settlement, illegal logging, hunting and other activities.”

Indigenous communities realize it will be tough to stop the march of “progress” through the jungles of Peru. But they’re demanding that the oil companies and the government at least improve their environmental standards and give them a chance to live safely in the rainforest, fishing, hunting and living in harmony with the land.

That has been a difficult goal to achieve for the communities living around Lot 1AB.

Pluspetrol, the Argentine company that produces close to 25,000 barrels a day from its concessions in the northern Amazon, is known for evading government clean-up orders.

In 2014 the company’s lawyers challenged a report by Peru’s Environmental agency, OEFA, that found 92 contaminated sites in Lot 1AB. The company argued before a provincial judge that OEFA had acted beyond its jurisdiction, and gained a court order that invalidated the reports’ findings.

“We need a stronger state, that stops these practices from happening” said Tami Okamoto, a Japanese-Peruvian negotiation expert who works with indigenous federations.

“They dried up a lagoon in Kichua territory on the Pastaza River, the company was fined 20 million soles [$7 million] but they managed to have a court overturn it,” Okamoto said.

Fusion emailed and repeatedly called Pluspetrol’s spokespeople to request comment on these incidents, but never received a response.

The company has, however, issued several press releases stating that it “shares the concerns” of indigenous communities. In February Pluspetrol reported it has spent $100 million in community-development projects during the 14 years it has operated in Lot 1AB, and that it has cleaned up more than 100 sites that were polluted by the previous concessionaire, Occidental Petroleum.

But Okamoto says the company acts in bad faith by sending lawyers into the jungle to individually negotiate settlements with indigenous villages, instead of settling problems with technical experts who have been appointed by indigenous federations.

Okamoto said that the Ministry of Energy has agreed to push Pluspetrol into officially recognizing the contamination found at the 92 sites documented in last year’s report before its lease runs out and it abandons Lot 1AB or seeks to renew its concession. But there is no guarantee that will happen.

“We hope those promises come through,” Okamoto said. “But we are worried because so far, Pluspetrol hasn’t mentioned those sites in their plans to surrender the lot.”

Indigenous communities along the Marañon are also worried about what’s going to happen.

Anderson Ordoñez, an environmental volunteer for the Kukama tribe trekked six hours into the jungle from the hamlet of San Pedro to show Fusion a mile-long spill along the Northern Peruvian pipeline in December.

Ordoñez said he fears that more production in the area will lead to more spills like the one that now threatens water supplies in the village of San Pedro.

“We need to tell westerners that the Amazon is also part of them,” Ordoñez said. “The Amazon is the lungs of the planet…it is our pharmacy, our hardware store. It is our life.”